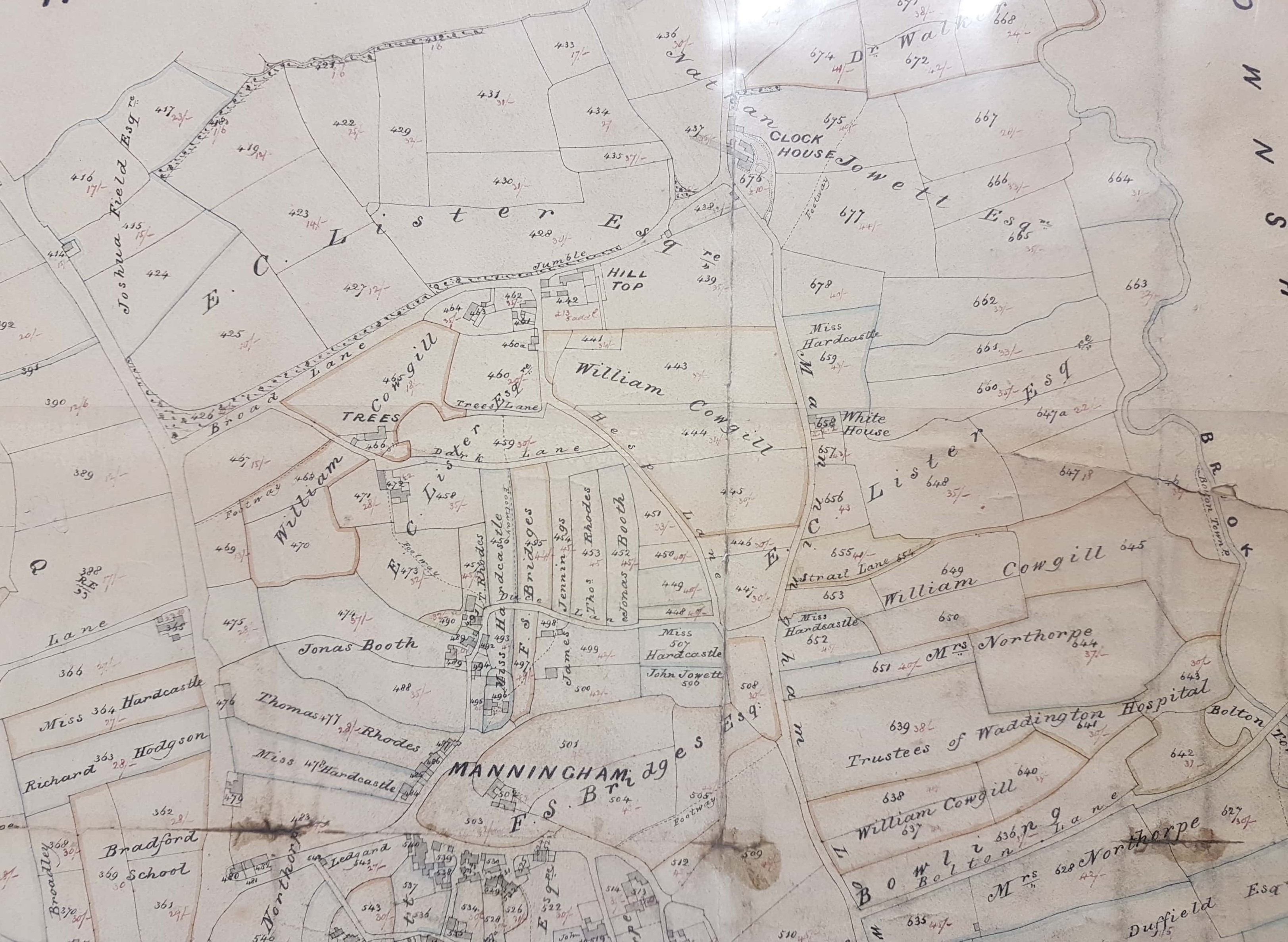

Several months ago I posted a map of Manningham village and commented on the creation of Manningham Hall, the long-demolished predecessor of the existing Cartwright Hall. This whole episode is a highly complex one, which touches on one of Bradford’s most celebrated 19th century families, and I should now like to provide a much more detailed account. To introduce it I have included this detail of a beautiful 1811 map of the area from the Local Studies Library permanent public collection.

For rather more than a century the grade II listed Lister Park has been Bradford’s premier open space, and the Cartwright Memorial Hall a distinguished home for its art collection. The Hall is a listed building, and a number of the park’s gates and statues have independent listing. I should like to explore the circumstances in which this public space was created and the fate of the buildings that had previously been found at this location. One of the barriers to easy understanding of these topics are the names assumed by two of the main characters involved. Lord Masham was born Samuel Cunliffe Lister and I shall use this name throughout, although it is incorrect after 1891: at least it clearly distinguishes him from an earlier Samuel Lister who is also highly significant to the story. Samuel Cunliffe Lister’s father was successively known as Ellis Cunliffe, Ellis Cunliffe Lister, and Ellis Cunliffe Lister Kay. I shall normally adopt the name Ellis Cunliffe Lister since it makes the relationship between father and son unmistakable. A second barrier is that there have been at least three buildings on approximately this site: Cartwright Memorial Hall, Manningham Hall, and a third which was evdiently known as Hill Top and might have also once have also been called Manningham Hall. The final difficulty is that maps of this area, which are my main interest, do not seem to correspond exactly to the received historical account.

The dates which encompass the creation of Cartwright Hall are clear since tablets in the entrance hall indicate that the foundation stone was laid by Samuel Cunliffe Lister (Lord Masham) in May 1900, and the building officially opened by the Prince of Wales (later King George V) in 1904, after which the building formed part of the great Bradford Exhibition held that year in Lister Park. The hall architects had been John W Simpson and E.J. Milner Allen who had also designed the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow. Personally I find the building too solid and ornate for my taste and the best features, in my view, are the four statues on the cupola representing: spinning (distaff), commerce (ship), fortitude (sword) and abundance (horn). These were executed by the sculptor Mr A Broadbent of Shipley, but are hard to adequately view without binoculars! The whole art gallery project was the product of the fertile imagination of Samuel Cunliffe Lister who donated a substantial fraction of its cost to Bradford Council. I understand that the erection overran, in terms of both time and costs, which is highly plausible for a large public project of this type. Samuel Cunliffe Lister suggested it be named after Edmund Cartwright who, as well as devising a power loom, made the first mechanical wool-comb: a predecessor of his own, more commercially successful, invention. The cynical view was that long-dead Cartwright was the only major textile figure with whom he had never had a bitter quarrel. His acrimonious debate with Sir Isaac Holden over who had invented one pattern of mechanical wool-comb even outlived Holden’s death! In fact, since the great Manningham Mills strike of 1890-91, Samuel Cunliffe Lister was a highly controversial figure within Bradford. Even his gift would have appealed more to the affluent middle classes, whom he probably saw as his natural allies, than to the weavers and spinners at his own mill on whose exertions, after all, his fortune depended.

The 22 ha public park in which Cartwright Hall sat had been progressively developed between 1870 and 1904 but was not finally complete until the opening of the gallery itself. There was an older ‘Manningham Hall’, also then owned by Bradford on an adjacent site, which was removed during the creation of Cartwright Hall. It is said that Samuel Cunliffe Lister was depressed by the neglected state of his former house during a visit in 1898 and his plans probably always involved its demolition, although the idea of replacing it with a dignified gallery and museum may have come quite late on. The state of his old home cannot really have come as a surprise to Samuel Cunliffe Lister. Lister Park had been in the possession of Bradford Corporation since 1870, and as early as 1875 the Bradford Observer reported that Manningham Hall was in a poor state and useless, ‘except as shelter from the rain’. There had been a decision by the Corporation to use the old dining room as art gallery for pictures produced by the Bradford Art Society. The previous year it was reported that ‘light refreshments’ were available there. Three years earlier still, in 1871, the Bradford Observer noted that the Corporation had sought tenders to turn Manningham Hall into a restaurant: before that plants had been sold there. In the early months of the Corporation’s ownership it looks as if some rooms were still habitable. Again the local newspaper noted, in January 1871, that Madam Bentley and ‘young French ladies’ were residing at Manningham Hall and had visited the Bradford workhouse: why is not explained. The Leeds Mercury in 1870 considered that the hall was not a very handsome building, but it was commodious and its use as a geological museum was suggested. Closure of Jumbles Lane, which bisected the park, was considered even at that early stage. You can make your own mind up about the appearance of the building in this illustration taken from William Cudworth’s: Manningham, Heaton & Allerton.

How had this state of affairs come about? It is a matter of public record that on 28 October 1870 the ownership of Manningham Hall and its estate had been transferred from the ownership of Samuel Cunliffe Lister to that of Bradford Corporation, whereupon its name had been altered from Manningham Park to Lister Park. At that time a new Manningham Mill was in the process of being constructed following a disastrous fire in the old mill. Samuel Cunliffe Lister had already removed from Manningham Hall to another of his family’s houses, Farfield Hall in Addingham (and he was eventually to leave the area altogether by purchasing a great estate in North Yorkshire). It is clear that his first idea was to sell the Park for villa development and in April 1870 an advertisement appeared in the local press to that effect, in which Captain Lepper acted as his agent. Manningham Hall was referred to in these adverts as ‘late residence of SC Lister’. This plan did not mature so he offered the estate and Hall to the Corporation for £40,000 with the proviso that it became a park. The sum involved was well below, perhaps 50% below, its market value but did not constitute a free gift as is sometimes stated.

The Lister family must have moved out only a short time before since as recently as October 1869 the Bradford Observer had reported that Mrs Lister had given birth to a daughter in Manningham Hall and was providing grapes for the Royal Infirmary from its hot-houses. Examination of contemporary newspapers make it clear that the estate had previously been offered for sale in 1868 and even at that time the purchase of the estate for a public park was suggested by correspondents and its central position, if ever Bradford and Shipley were amalgamated, was noted. (This union only finally came about in the Local Government reorganisations of 1974). We can reasonably assume that in the 15 years 1853-1868 Manningham Hall had functioned as an ordinary, but substantial, home for Samuel Cunliffe Lister and his family, being conveniently placed for Manningham Mill, the town, and Frizinghall railway station.

In the first half of the 19th century the owner of Manningham Hall had been Lister’s father, Ellis Cunliffe Lister who had died there in November 1853, having reached his seventy-fifth year. Ellis Cunliffe Lister had been married three times and had four sons who adopted various combinations of his complex final surname. The most famous was of course Samuel Cunliffe Lister who eventually succeeded to the Manningham Estate. Samuel’s acquisition of Manningham Hall was brought about by events occurring a decade earlier. In 1841 Ellis Cunliffe Lister’s oldest son and heir, William Cunliffe Lister MP, died suddenly before even taking his seat in Parliament. The next son, John Cunliffe Lister of Manningham Mills, retired from business and went to live at Farfield Hall, Addingham and then, finally, Kent. Samuel Cunliffe Lister was already active in the textile trade and it was intended that he should receive Manningham Hall and estate as his portion of his father’s considerable wealth.

Ellis Cunliffe Lister lived at Manningham Hall between 1819 and 1853 but actually acquired it in the late 18th century. I think that it is reasonable to assume that he slowly improved his property during his period of ownership. There are press accounts of his planting trees in the area facing Manningham Lane. There was also a reorganisation of the estate, from farmland attached to Hill Top, which you can see on the first map provided, to a gentleman’s park and residence with Manningham Hall at its heart. I don’t completely understand the account of Victorian historian William Cudworth but he seems to say that there was a land exchange in the life time of Ellis Cunliffe Lister with another local land-owner, William Cowgill, whereby Lister got a farmhouse called ‘The Trees’, which made his whole estate more compact. James Ambler, an early partner at Manningham Mills, resided at The Trees for a number of years. The land sale may be slightly more complicated since it may be Ellis’s son John Cunliffe Lister who nationally did the purchasing and then ultimately sold The Trees to his brother Samuel Cunliife Lister, but in any event the mid-19th century was a period of consolidation and improvement: all this property and several adjacent fields are now part of modern Lister Park. A small fragment at the extreme north-west remained as part of Heaton’s Rosse Estate and Heaton Reservoir was constructed next to this, across from the Heaton end of North Park Road, in 1876.

Cudworth further states that Ellis Cunliffe Lister originally moved to Manningham Hall in 1819. This does seem to be correct since there is a press notice of his second wife giving birth at Calverley House in 1818, and Calverley House being available to let in 1820. How had he acquired the house and estate? Ellis Cunliffe Lister began life as plain Ellis Cunliffe of Addingham, son of John Lister, being born in 1774. John Lister was reputed to be the first man to spin worsted yarn in Bradford mechanically. Ellis Cunliffe built several textile mills including Red Beck Mill, Shipley (1815) which he worked himself, and he lived initially at Calverley House. He married his cousin Ruth Myers (whose mother was born a Lister), and combined their two surnames in 1809 under the provisions of his father-in-law’s will. Ruth was the heir of her uncle Samuel Lister who lived at, and may have created, Manningham Hall before dying in 1792. In default of male heirs Ruth inherited his property but sadly she died young after only two years of marriage, it was therefore her husband who obtained Manningham Hall and its estate. Ellis Cunliffe Lister’s second wife was Mary Ewbank, the only daughter of William Kay, of Haram Grange in Cottingham. They were married in 1842, and to benefit from a further legacy Ellis Cunliffe Lister then became Ellis Cunliffe Lister Kay. He eventually married for a third time.

When Ellis Cunliffe Lister married Ruth Myers in 1795 they were already distantly related. Cudworth (I assume following John James) attributes this to a man called John Lister (1650-1734) who married Phoebe in 1690. One of his sons was Thomas Lister, vicar of Ilkley until he died in 1745, and another was John Lister of Manningham, who died in 1767. Now the vicar married Mary Bolling and one of his daughters, Elizabeth, married Ellis Cunliffe of Ilkley, the father of John Lister of Addingham and grandfather of Ellis Cunliffe Lister. Whereas John Lister of Manningham married Mary Field in the 1720s. I assume Mary was a member of the Field family of adjacent Heaton. She might have been the sister of John Field and thus aunt of the famous Squire Joshua Field, but I’m not certain of this. It is certain that John and Mary Lister had a son, Samuel Lister (1728-1792), who lived at Manningham Hall and died there without issue. They also had a daughter Elizabeth who married Joseph Myers of Leeds and herself had a daughter, who was Ruth Myers. My skills as a family historian are limited: I’m not sure if Ellis Cunliffe Lister obtained the estate as Ruth Myer’s husband or because he was the only surviving male in Samuel Lister’s immediate family. Nor do I yet know why he did not live at Manningham Hall between his marriage to Ruth, in 1795, and 1819. One possibility is that Ruth didn’t inherit immediately on her uncle’s death, or perhaps the property was unsuitable as a gentle man’s residence and needed years to pass before improvements were completed.

Be that as it may the crucial figure in this whole story is Samuel Lister who is considered to be the man who started the change from farm and farmhouse to estate and hall around in the last quarter of the 18th century. Samuel Lister is widely believed to have demolished an old Manningham Hall. The English Heritage listing document states that Manningham Hall replaced a building some distance to the north-west (of Cartwright Hall) in the 18th or early 19th century. This area is marked ‘William Lister House and Grounds’ on an 1613 map, which takes the link between the modern park and the Lister family way back into the early 17th century at least.

Map evidence

The 1908 Ordnance Survey map (not included here) shows the art gallery and museum completed and the park itself in very much its modern form. The large boating lake had been created to provide work for the unemployed and was never a natural feature. The boundaries of the park are Manningham Lane, Emm Lane and North Park Road. Substantial villa development has taken place around the park and nearby are rows of terraced housing.

As you can see things are very different in the first OS map of the district (1852) which was being surveyed in the late 1840s towards the end of Ellis Cunliffe Lister’s period of ownership. The area we think of as the park was bisected by Jumble Lane. South of this is marked ‘Manningham Hall’ which consists of four buildings, the largest I assume being the hall itself which is aligned on a carriage drive. I think you must have approached the Hall up the drive which extended from a lodge near from the modern Oak Lane / Manningham Lane junction. The front of the building faced east, looking over the Clock House Estate, and the Bradford Beck and Canal, to the airy uplands of Bolton. To the north-west is an ornamental deer park. (I’ve never seen deer in Lister Park but roe deer are still regularly seen in Heaton Woods, about a mile away). North Park Road does not as yet exist but a thoroughfare called Hesp Lane joins Manningham Lane to Jumble Lane and was apparently later extended to create North Park Road. There are few habitations near the hall aside from the Spotted House, Clock House, Carr Syke and the Turf Tavern, and the Trees farmhouse. All of these except the last survive in some form.

The Bradford Local Studies Library has an 1811 map of Manningham, with which this account started, and in which things look very different. Ellis Cunliffe Lister was still the owner at this time and since land ownership is indicated it is easy to see how much property he has. The site of Manningham Hall is not labelled as such but is rather still called Hill Top. The larger building present on the 1852 OS map is not present. The land south-east of Hill Top is the property of William Cowgill and it is this land, as well as Trees Farm, which was presumably exchanged as William Cudworth describes. Other large land-owners are ‘Squire’ Joshua Field of Heaton Hall and Nathan Jowett of Clock House. The LSL also has an undated and unlabelled map of Manningham, already shown in this series and of which I have now included a detail. It was once assumed to be a copy of the 1811 map but is certainly later.

This also shows the carriage drive and the building constructed since 1811. The large gardens are more fully drawn. This new building is linked to the old by a curved structure. This is also the same arrangement shown in the 1844-46 Thomas Dixon map of Bradford but thereafter the linking building disappears.

The final map in the series is also in the public collection and is also dated 1811. The quality is extremely poor but it does seem to show a building in the position of Manningham Hall although again it is named as Hill Top.

Interpretation

There is no doubt that this branch of the Lister family had lands in Manningham from before the time of the English Civil War. In the 18th century John Lister of Manningham married Mary Field, and their son Samuel Lister (1728-1792) owned the estate in question which was then known as Hill Top, and died there without issue. The question is: did he build Manningham Hall? The historical accounts say that he did but the map evidence suggests otherwise. The 1811 map still describes the location as Hill Top, not Manningham Hall, nearly 20 years after Samuel Lister’s death. He may have improved an existing building but this map evidence suggests a major construction of a building and a link to an existing structure was being built around 1811, with further alterations before the late 1840s. If Ellis Cunliffe Lister created Manningham Hall himself it certainly explains why his occupancy was delayed until 1819. The earliest example I have found of Ellis Cunliffe Lister using Manningham Hall as an address is in the 1822 Baines West Riding Directory.

Ellis Cunliffe Lister’s house and deer park seemingly had an existence of about 50 years: possibly it was the very huge business success of his son Samuel Cunliffe Lister that led to his departure from the Hall, but massive villa and terrace development in the surrounding areas may have rendered it a less suitable elite dwelling in any case. After Bradford acquired the estate in 1870 I’m not sure why the conversion of the Hall to an art gallery or museum was never seriously entertained, even though the suggestion was made. The present day Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley shows how successful this approach might have been. In the event 115 years ago Bradford got a new, rather expensive, but purpose built structure which has a considerable presence and is a much loved building in a much loved park.

References

If you would like to read modern accounts of Lister Park I can recommend:

Anne Bishop, Cartwright Memorial Hall and the Great Bradford Exhibition of 1904, Bradford Antiquary, 1989 see: http://www.bradfordhistorical.org.uk/cartwright.html

Simon Taylor and Kathryn Gibson, Manningham: character and diversity in a Bradford suburb, English Heritage, 2010.