On many occasions I have mentioned the difficulties of working with maps and plans that are undated, and of uncertain purpose. Even if those difficulties are resolved a third problem sometimes occurs, which is deciding if features on the plans actually exist, or existed, or were perhaps simply speculative gleams in the eyes of planners and developers. Some plans of Peel Park found in the Local Studies Library reserve collection illustrate this problem very well.

Peel Park is Grade II* listed, 56 acres in extent, and was named after Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) after his death. Peel was the PM whose government legislated against child labour in mines and factories. As Home Secretary he created the police force, and he and his supporters later joined with Liberals and Radicals in 1846 to reform the existing, and harsh, Corn Laws. This reform resulted in the import of much cheaper grain supplies which benefitted the poor. I’m not sure what combination of these achievements endeared him to the prominent citizens of Bradford when they met to plan a memorial within a few weeks of his death. Peel had suffered a horse-riding accident which was reported in the Bradford Observer on 4 July 1850. Announcement of his death followed later the same day and he was buried on 11 July at Drayton Bassett, his family having declined a public funeral.

The Bradford park which carries his name was opened to the public in 1853. It is significant since it was such an early example of a public park. Joseph Paxton’s design at Birkenhead is generally accepted as the first in England, being opened in 1847. The group that financed Bradford’s first example initially retained control and weren’t, for financial reasons, able to present it to the Borough of Bradford until 1863.

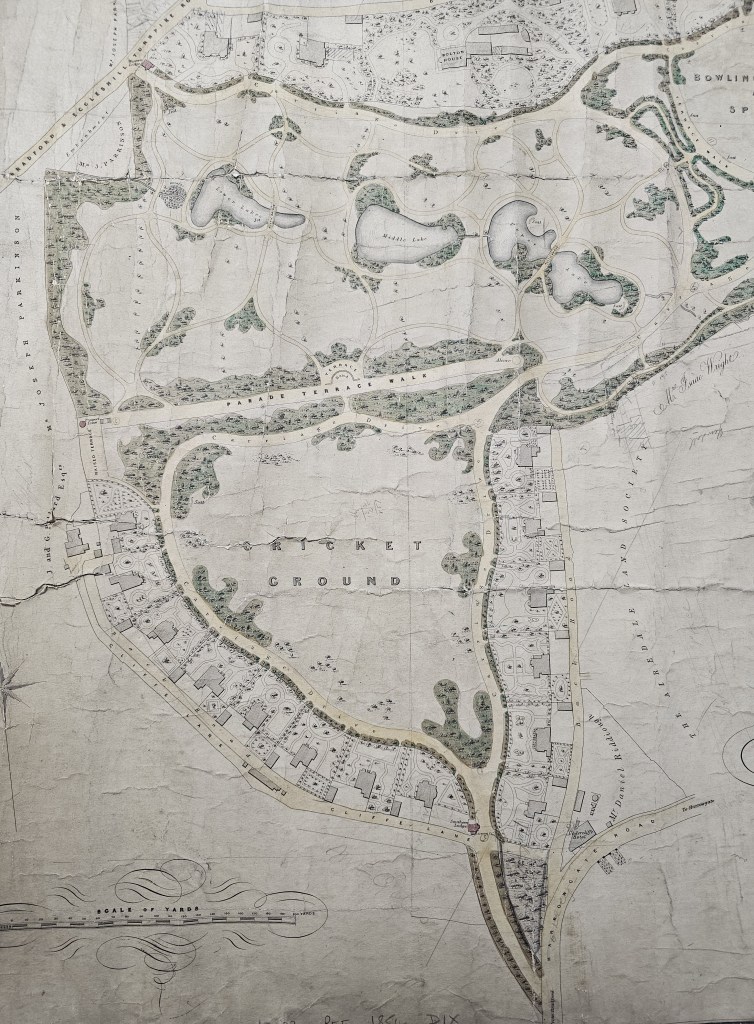

I have been working with three plans, supplemented by OS maps of the area. All were surveyed and drawn by professional surveyors. The 1854 map (figure 1) was drawn by Bradford surveyor Thomas Dixon and is annotated in pencil. Three substantial lakes are indicated: Lower, Middle and Upper. Both the Lower and Upper Lakes are divided by rustic bridges, which can be seen well in the detail which forms the second figure.

It is not possible to confirm this arrangement in the 1852 6” OS map since the park was not then in existence. When I used this first image on social media local historian, Paul Whitaker, queried the existence of the Upper Lake. It is not present now, nor was it present on the 1893 25” OS map of the area: he very reasonably wondered if it was a purely hypothetical lake.

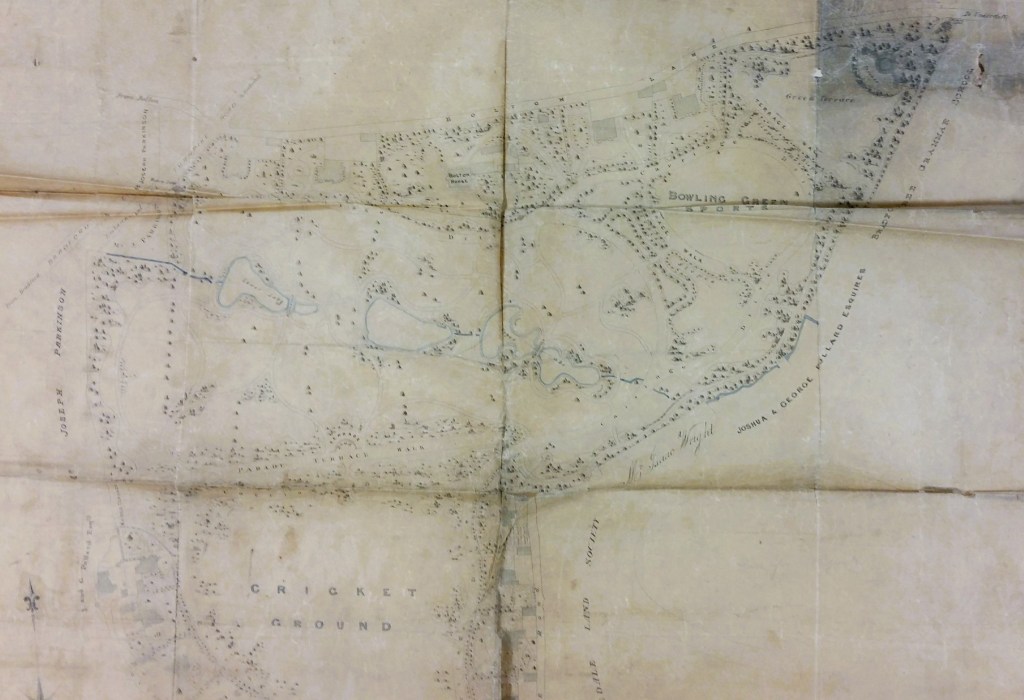

We have this second map (figure 3). It was also drawn by Thomas Dixon, but on tracing paper. You can see it is a close copy of the 1854 map already provided, but it is not an exact facsimile. The Middle Lake is not named and there are a small number of other differences. For what it is worth the Upper Lake is quite clearly present here.

The final map from 1884 was drawn by J. Clifton, surveyor of Manchester. It is so large that I had to photograph it in sections. It would appear that the Lower and Middle Lake have survived the thirty year period, although with changes of shape. There have been dramatic changes to the pathways around the old Upper Lake, with only a small fragment of standing water remaining; this too has vanished by the time of the 1893 25” OS map from about a decade later. I assume that the modifications would have commenced after the change of ownership in 1863 when the Borough of Bradford acquired the site.

Paul Whitaker himself cleverly resolved this conundrum with modern technology. LiDAR data is now available for this area and provides good evidence for the three original lakes. I’m anxious not to infringe any copyright by reproducing the image but if any reader is interested simple go to the excellent ‘ARCHI LiDAR and Explorer’ website and put in a nearby postcode, such as BD2 4AA.

Paul may have been converted to the three-lake arrangement but was certainly not convinced by another feature of the original 1854 map: the villa development around the cricket ground, shown in the next map detail.

The 1893 OS map does not show the carriage drives and the elegant villas. The choice lies between the buildings having been demolished within less than 50 years, or agreeing that they were never constructed at all. This second option seems far more plausible. There is simply no end to the information contained within old maps and this was a welcome opportunity to undertake an exploration project with a more knowledgeable critic.