1.19 WIL c.1850 PLA

Material: Cartridge paper Scale: unk

Size: 38*68 cm Condition: Good

This map was used as an early ‘map of the week’, but more information has now come to light. I must stress that every source of information used to prepare this article is available easily, and absolutely free, to the interested local historian. Sources are the Bradford Local Studies Library, the West Yorkshire Archives, or on-line. To the best of my knowledge all the images feature essentially the same area of Norre, Nor, or Norr Hill, Wilsden, although the orientation of the images is not identical.

Few, if any, districts of Bradford are unmarked by some evidence of old mining activity. In the northern part of the community coal exploitation had long been undertaken in the townships of: Heaton & Frizinghall, Shipley & Northcliffe, Baildon, Idle, Eccleshill, Thornton, Clayton, Denholme, and certainly Wilsden. In his account of Wilsden Cudworth quotes the Bingley register: ‘Thomas Illingworth of Cottingley, who dyed in a colepitt at Norre, with a dampe. August 1594’. This would make the make the unlucky man Bradford’s first recorded mining victim. A dampe is a mining term for a gas. In this instance it might well be carbon dioxide which can accumulate in inadequately ventilated mine galleries.

Naturally Wilsden is covered by the first OS map from around 1850. The Bradford Local Studies Library have two additional mine plans from the area, of which the first shown is an example. West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) have large maps displaying all the coal mining activity distributed across the area. For example, there is a plan (WYB346 1222 B16) of Old Allen Common in Wilsden, including its collieries. This shows the area where Edward Ferrand Esq of St Ives, as Lord of the Manor, had mineral rights over common land. This map was ‘made for the purpose of ascertaining the best method of leasing the coal’ by Joseph Fox, surveyor, in 1829. The collieries named were operated by Padgett & Whalley, and Messrs. Horsfall.

The way in which the coal mine included in the first map functioned is easier to understand if I enlarge the image. Although the map is undated there is an annotation which reads: ‘Soft Bed accessed by inclined plain’. The Soft Bed is a coal seam, in fact the deepest commercial seam in the entire Coal Measures, which lie conformably on top of the Millstone Grit series of rocks. An inclined plain is a drift mine: these were common locally but seem to have been a relatively late development here, perhaps as late as the mid-nineteenth century. Before this time shaft mining was the customary way of accessing the coal seams. The map has no indication of the owner or occupier but Cudworth states: ‘coal mines worked by Messrs Isaac Wood & Son, both at Norr Hill and Pudding Hill’.

By whatever method you accessed the seam the coal was removed through galleries, with large pillars of the mineral being left to support the roof. The ‘take’ was perhaps 60% at best. If you are sharp-eyed you may be able to make out the words ‘geal (or goul) 4½ yards down to south’. This must be a local mining dialect term indicating that a geological fault interrupted the seam: faulting was very common locally and made it difficult for miners to follow the same seam from place to place.

Any working coal mine would need to be drained and also ventilated. Drainage was often achieved by digging a long underground channel or ‘sough’ to take water to a lower level surface watercourse. As well a shaft to access the galleries a second ‘air’ or ventilation shaft was often sunk. In operation active men were needed as ‘getters’ to hew the coal. As the seams were thin this must have been undertaken in a lying or kneeling position with illumination provided by only flickering candlelight. Hewed coal was then conveyed in wicker baskets, called corves, by ‘hurriers’ to the nearest shaft bottom. If they were physically capable children and women could fulfil this function, although women working underground were seemingly becoming rare in the Bradford area by the early nineteenth century. The full corves of coal could be extracted by a hand-windless or, if the shaft were deep, a horse gin, and then removed by carts or packhorses along an extraction track to the nearest roadway.

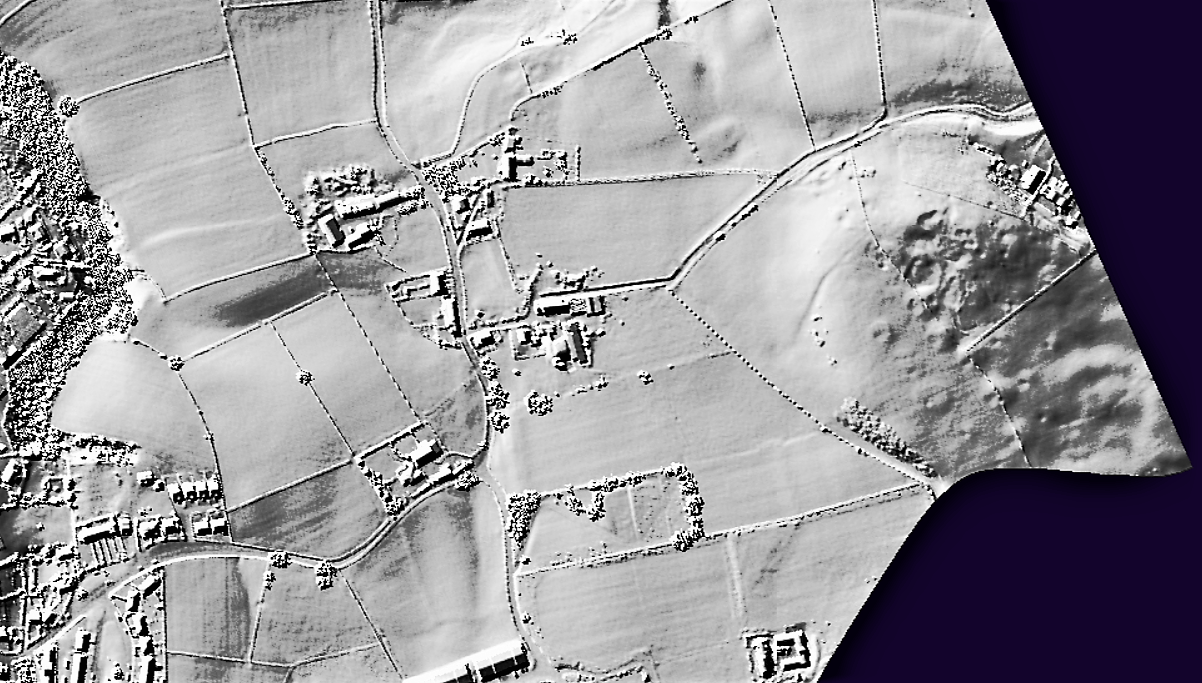

So, what new evidence has become available? LiDAR coverage is patchy in this area. Northcliffe Woods are covered, but Heaton Woods are not. Fortunately, the Wilsden coverage just stretches as far as the bulk of Norr Hill. Here you can see that the hill crest is covered by a network of regularly placed shafts, each capped shaft being surrounded by colliery spoil.

See: https://www.lidarfinder.com/

This pattern is far less obvious in a Google Earth aerial image, although this application is also an immensely useful facility for the amateur archaeologist.

Unfortunately, these visible remains are not those of drift mining so they are not explained by the original map. I presume that the seam about 20m above the Soft Bed, known as the Hard Bed, was accessed (almost certainly at a much earlier time) by superficial shaft mines – a technique often called ‘Bell Pit’ mining. Indeed, it may be the disturbed ground resulting from the ‘old men’s work’, was seen to make a deeper shaft sinking hazardous, which in turn determined the construction of the later drift mine.

To men labouring as miners in the early nineteenth century the coal extraction industry must have seemed timeless. Could they ever have imagined that in 2015, with the closure of Kellingley Colliery, the deep-mining of coal in Britain would be brought to an end?

Another very interesting piece – thank you.

Again with reference to Irish landowner (Ferrand).

Also – Old Allen Moor and the bell pits referenced in the tale of Fair Becca, whose man ‘did her wrong’, so she haunted him…

LikeLike