Recently I attended the AGM of the Friends of Judy Woods. I was lucky enough to hear a presentation on early coal mining given by Dr Ron Fitzgerald, who was once director of Leeds Industrial Museum. Dr Fitzgerald has considerable experience of early mining, which includes actual excavation with the radiocarbon dating of recovered organic materials. He is rightly highly suspicious of those who attempt to reconstruct the extent and practices of the industry solely on the basis of historical sources. Can maps contribute to reconstruction efforts?

The earliest ways of coal recovery, from seams close to the surface, was simply quarrying down to the seam by removing the overburden. A more sophisticated technique was the construction of Bell Pits, where a shaft was expanded at the base by the removal of coal until the pit became unstable. Both such techniques are largely medieval and may have been undertaken on Baildon Moor, even if the majority of shafts there are of a later date.

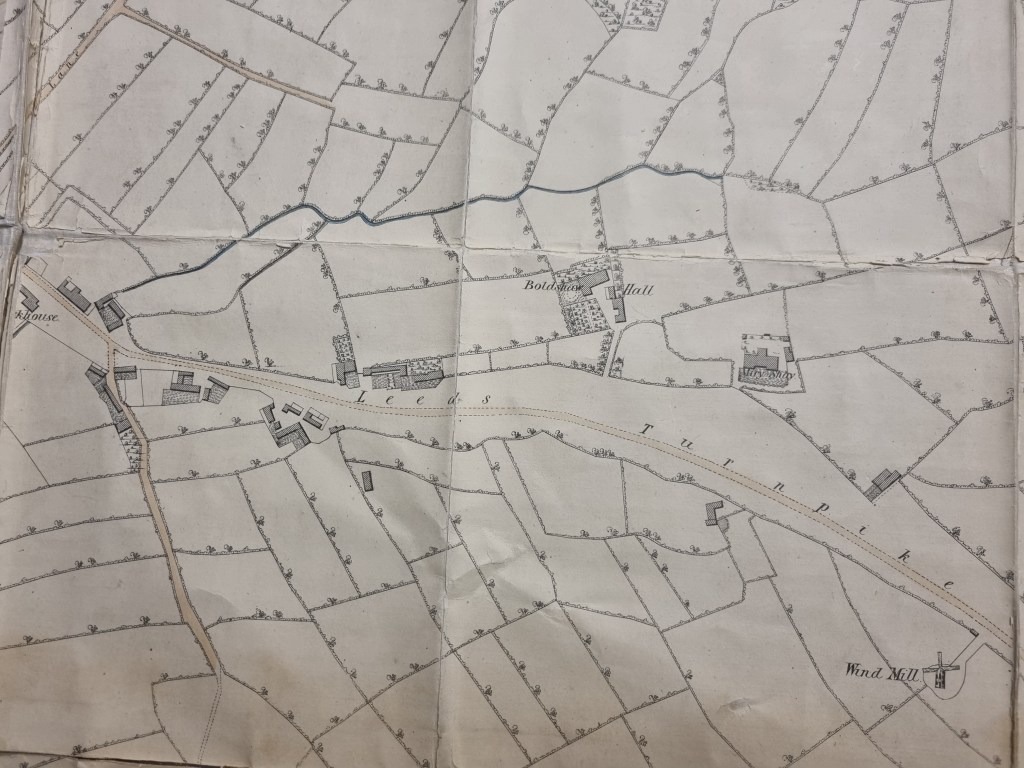

The earliest mapped coal exploitation that I know of is from the Bradford & Horton map of 1722 of which the first figure is a detail. Several annotations north of Great Horton read ‘coal pit’ or ‘pit now working’. It seems highly likely that every unannotated dot on the map represents a shallow shaft pit. If this interpretation is correct the extent of Bradford’s coal industry in the late 17th and early 18th century must have been considerable.

Water ingress is the great enemy of mines and I wondered how the drainage of such pits was effected. Dr Fitzgerald suggested for a relatively shallow Bell Pit that simply digging a sump would be sufficient, with the water being brought to the surface by bucket and chain.

The 1802 map of Bradford does not show evidence of coal mining even if the area examined, like this location along Barkerend Road, was later noted as the site of a substantial pit. The map surveyor may have simply ignored quarries and pits, or possibly such industries were then confined to outer areas like Horton and Heaton which do not feature at all since they were not then considered to be part of Bradford.

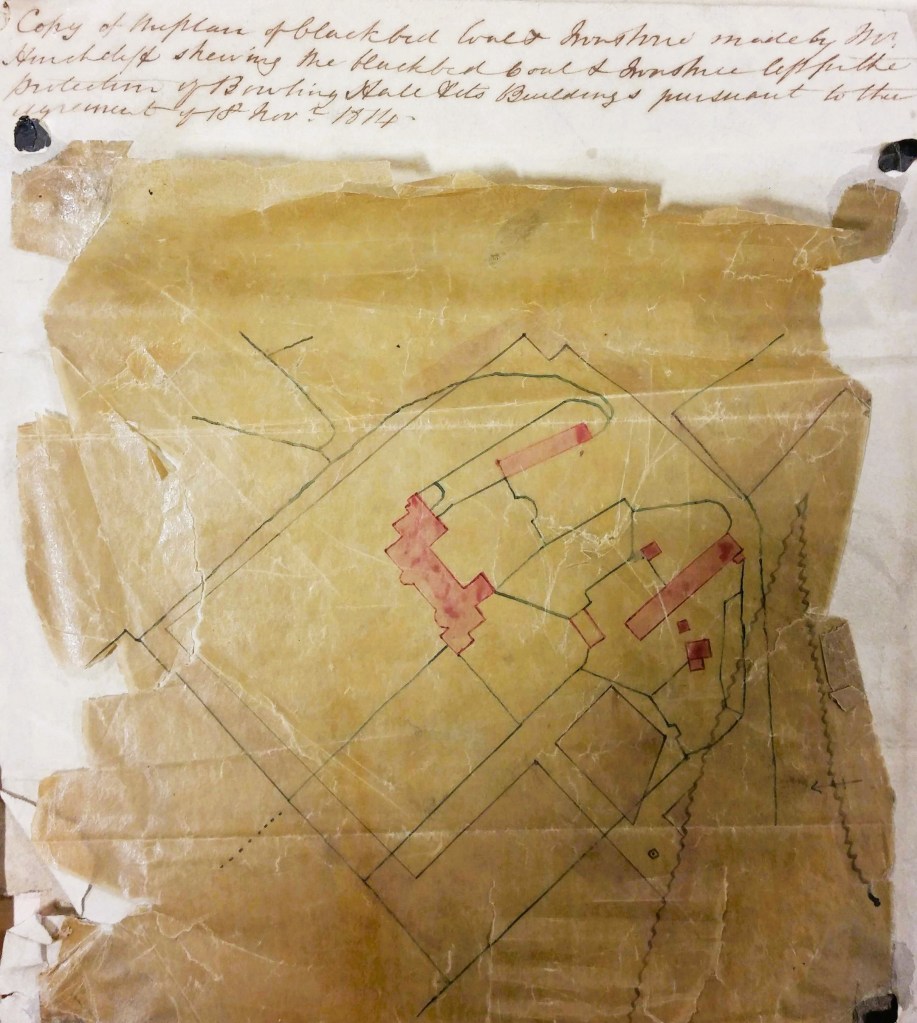

That a sophisticated contemporary mining industry existed is evidenced by my favourite reserve collection plan from 1814. the plan is headed: ‘Copy of the plan of Black Bed coal and ironstone made by Mr Hinchcliffe showing the Black Bed coal left for the protection of Bolling Hall and its buildings pursuant to the agreement of 18th November 1814‘. Pink blocks represent Bolling Hall and its attendant out-buildings. Many of the black lines are property and field boundaries. Some of these make sense today, others presumably delineate parcels of land associated with the out-buildings. This whole central area is slightly paler in colour than the region outside the precinct boundary, which is darker and I assume represents winnable coal. The wavy line, in an inverted V shape to the right, is probably a geological fault. In his description of the area historian William Cudworth reported a Bolling Hall fault which threw minerals ‘down 28 yards to the south’. The removal of the Black Bed and its ironstone naturally left a gap into which the overburden of rock could collapse, resulting in surface subsidence. The common practice was to leave pillars of minerals unmined to support the roof. Under especially sensitive areas, which included churches and the mine-owner’s house, no mining at all took place. To indicate such restraint must be the purpose of this plan.

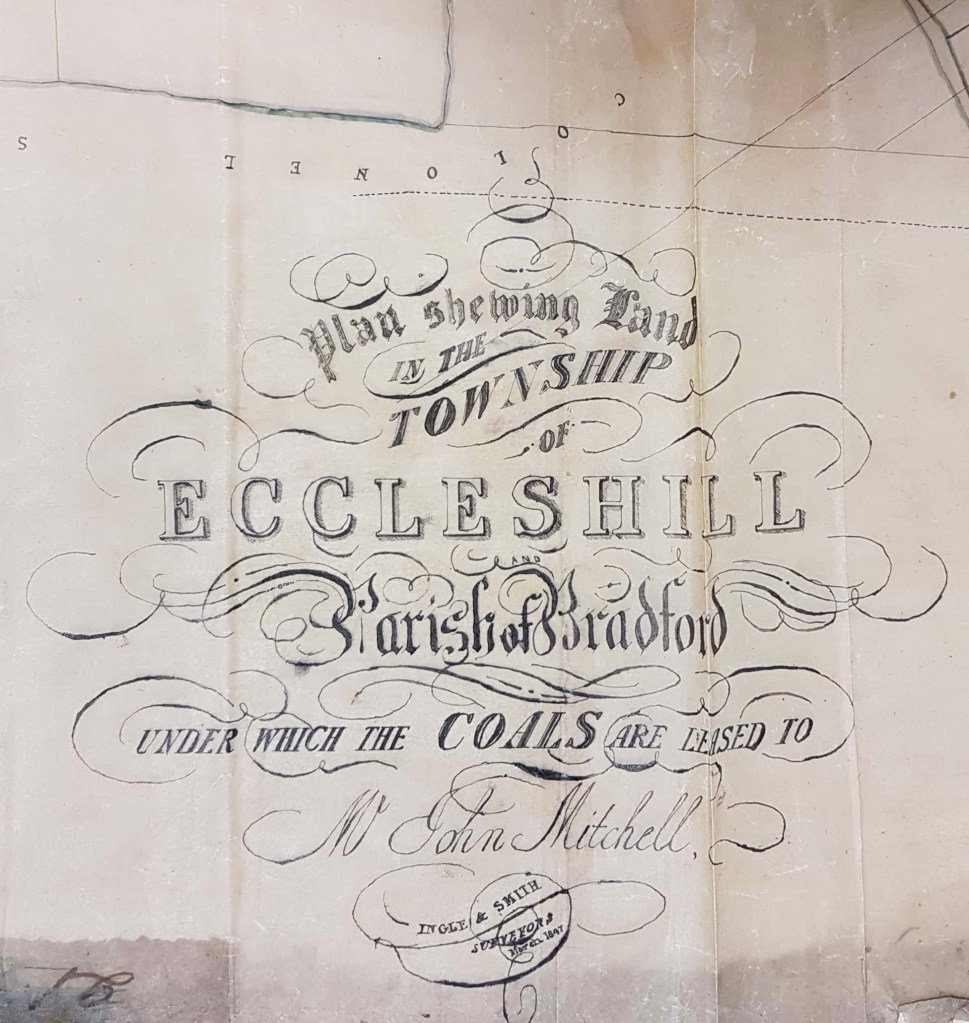

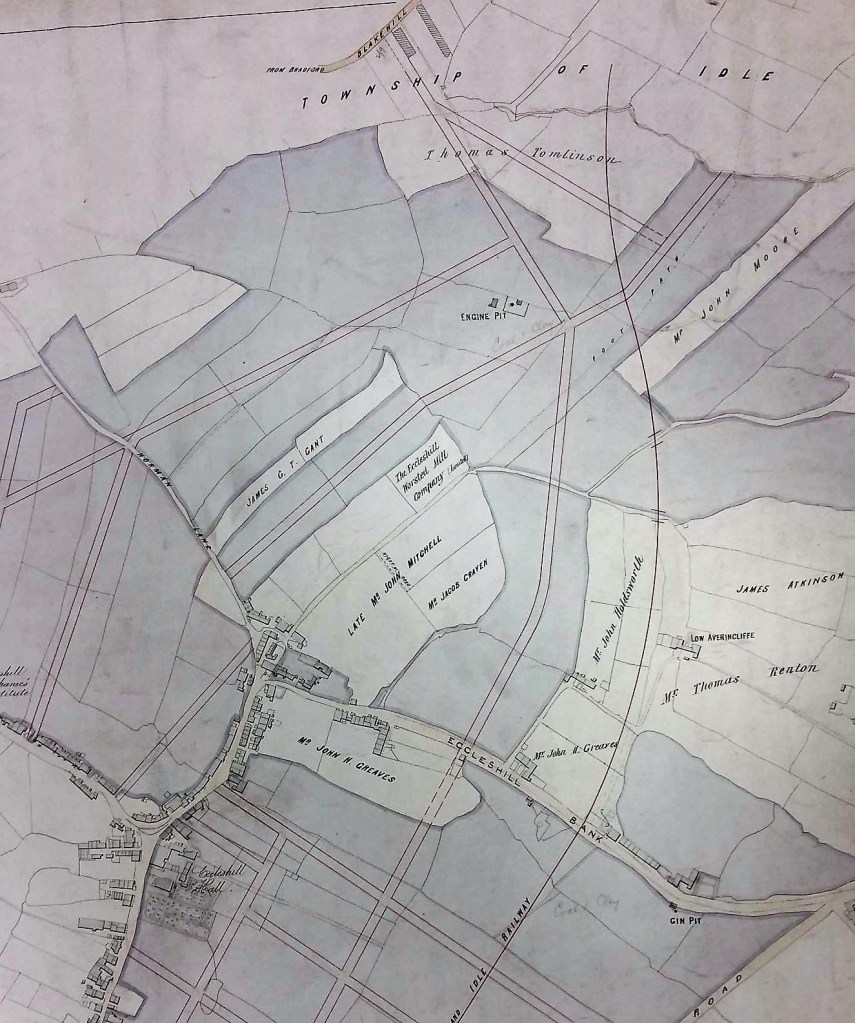

A generation later (1847) there was a substantial coal mining industry in Eccleshill, with shafts and galleries. Evidently landowners leased the right to exploit the seams to John Mitchell. Eccleshill historian Ken Kenzie told me that John or Jonathan Mitchell was a coal merchant who once lived at Eccleshill Bank. He was clearly a big man in Eccleshill mining and, among others, ran Park Pits which were sold off in 1860 when he was in his 70s.

I don’t know Eccleshill well enough to completely interpret my next two maps. The detail above indicates that John Mitchell has now died and shows the location of an engine pit and a gin pit on Eccleshill Bank. It is obvious that a planned street grid has been superimposed on an older map, but I do not think that all those roads were actually constructed.

This detail shows both surface and underground features. ‘Galls’ (sometimes spelled as ‘Goals’) are geological faults. The West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) has a huge collection of Jowett family documents (10D76/3/190). In box 6 of these is a lease dated 1842: ‘George Baron to John Mitchell, Eccleshill’. This document is a 28 year lease of Upper Bed and Lower Bed coals in the area of Greengates, Eccleshill. The price seems to be £60 per acre. This is somewhat north of the area discussed so far, but Greengates and Apperley Bridge were traditionally considered to be part of Eccleshill.

I am concluding with two more favourite maps. The above detail centres on Barkerend Road. Slightly left of centre is the location of a colliery. It is undated but by the time of the 1852 Ordnance Survey map there was a large colliery just south of Miry Shay called Bunkers Hill. I believe that, in this period at least, Rawson, Clayton & Cousen operated it. The name Bunkers Hill seems in fact to be applied to a series of collieries along Barkerend Road. The spoil pits they left behind were used by local children as unofficial playgrounds until the 1960s.

Our best colliery map is this one from Old Allen Common at Wilsden. You cannot ask for much more. Galleries are shown; old workings and faults are identified. Two active pits are described (Jack and Jer). Even the coal seam exploited is named: the Soft Bed, which is the deepest commercial seam in the whole of the Coal Measures. If only there were plans like this for all Bradford’s mines.