The use of this title for a district of Bradford doesn’t pre-date the foundation of the famous Low Moor Iron Company (LMIC) in 1790. Wibsey Moor, Wibsey Slack or North Bierley were the previous descriptive names. In 1828 or 1829 surveyor Joseph Fox drew a map recording all the property of the Low Moor Iron Company. The West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) have copies of his map, generously donated by Geoff and Mary Twentyman who, together with the Low Moor History Group, have done so much to research and record the history of this area. Fox drew other maps; the LSL reserve collection also contains a beautiful example showing Harden Moor, with the roads connecting Keighley and Bingley, surveyed in 1830.

Presumably versions of the Low Moor map were altered or annotated to reflect changes, and it would seem highly likely that at least one copy of the map was kept on display at the ironworks. The Local Studies Library reserve map collection also has a plan, labelled North Bierley, which closely resembles the Fox map. It has deteriorated quite badly but the detail included as Figure 1 is perfectly clear. The same landowners are mentioned although the script in which their names are written differs. The plan of the Low Moor Ironworks is identical in the two maps, as are most of the buildings included.

In the top left corner of the image are a collection of roughly circular features. These represent coal or ironstone mines. It is hard to imagine now that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Bradford was densely covered by mines, abandoned mine-shafts and piles of colliery waste. The Low Moor and Bowling Iron Companies smelted iron ore, obtained locally from the roof of the Black Bed coal seam, using coke made from the deeper Better Bed seam. The production of cast iron and ‘best Yorkshire wrought iron’ was extremely profitable for more than a century.

In the approximate centre of the map is the place name ‘Glass House’. This represents the site once occupied by Bradford’s only known glass-making furnace. The builder of the glass-works, known to be in existence by 1748, was Edward Rookes Leeds (1715-1788) of Royds Hall, Lord of the Manor of Wibsey. In that era the space needed for a furnace and its attendant glass-workers was enclosed by a brick cone, and there were large underground flues. The Fox map in the WY Archives places a large circle at this site which could easily represent a glass cone in plan, but the map illustrated here has no such feature. The two map versions have ‘caught’ the brick cone in the process of being demolished.

Figure 2 is a detail of the first Ordnance Survey map of the area. A section of the main works is top left but the detail also shows the New Biggin Works, which the LMIC created, and the Bierley Foundry which was originally independent but which LMIC acquired by purchase in 1854. The Bradford Local Studies Library has some late nineteenth century images taken at all these sites.

These cannons are at Low Moor itself. They would have been obsolete at the time the photograph was taken, but illustrate the importance of the works in arms manufacture. I have seen a Low Moor cannon myself at Alnwick Castle or possibly Berwick.

The image quality of the next figure is not good, but it clearly shows two blast furnaces at New Biggin. To the right is an obsolete stone-built example. On the left is a more modern furnace with a steel constructed stack. In both cases the furnace would be fed at the head with ironstone, coke fuel and crushed limestone (to remove silica as slag).

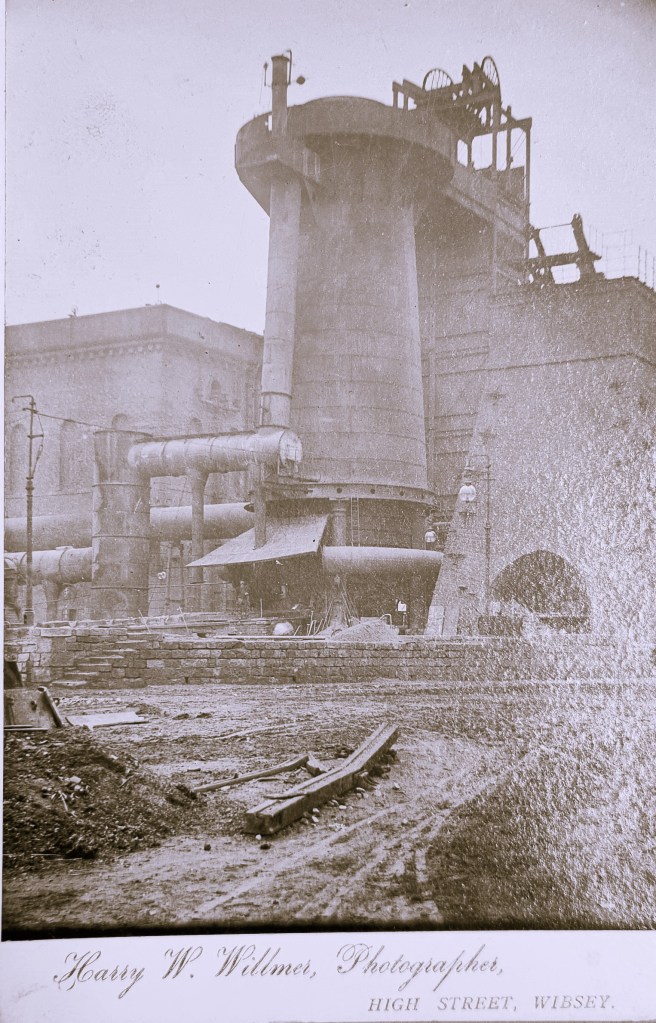

The final photograph is of a stone furnace at Bierley Iron Works taken at the time of its demolition. The stacks of all blast furnaces would require lining with refractory bricks made of fireclay or ganister. Both minerals were the products of local coal seams as was the coke and ironstone. Once local minerals were exhausted it was too expensive to transport imported supplies from the seacoast ports, and all inland ironworks were doomed.

The Reserve Collection has other relevant plans. Figure 6 records an intention to construct a loop line from the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Bradford-Halifax mainline to service a portion of the Bierley Ironworks, at an estimated cost of £2152. This would pass through an old embankment and round a reservoir. The area involved is immediately east of Wesley Place and the L&YR track involved is just south of Bowling tunnel. An earlier, but anonymous, student of the plan has provided us with a date of 1874 which I have no reason to doubt. The new track arrangements were certainly in place by the time of the 1889 Ordnance Survey 6 inch map. The value of this plan lies in the works details recorded: ironstone staithes, coal staithes, Better Bed staithe near to the coke ovens, limestone staithes, and dross staithes. Staithe is a dialect word meaning a storage area or a landing stage for loading or unloading cargo.

The end-product of this whole smelting process were pigs of cast iron. This could be remelted in a puddling furnace to produce the best Yorkshire wrought iron for which Bowling and Low Moor were famous. Wrought iron was subsequently replaced by cheaper and stronger mild steel, and is no longer produced.

The last map detail is really best inverted to put north at the top, although I have not done this so that the annotations can be read. It shows an area immediately north-west of New Biggin and due south of Glass Houses (which is drawn but not named). The railway line is curving round to enter Wyke tunnel in the direction of Lightcliffe. The main feature is a short tunnel that allows a coal railway or mineral way to cross the rail tracks. The terraced housing is at Morley Carr and you may be able to make out a New Biggin Bridge that must have allowed pedestrian access to the foundry site.

The production of waste slag at all the ironworks was so great that dross hills or mountains were produced. The glassy material was not without its uses. It could be broken up and used as a hard-core foundation for tracks and roadways It can still be found today all over Bradford even if supply probably once greatly exceeded demand. It has long outlasted the furnaces that once produced it.