We pity the plumage but forget the dying bird, is a phrase of Thomas Paine’s used to describe the indifference of affluent Victorian society to the privations and living conditions of the working class. Although Bradford did not have a Peterloo massacre it was, on several occasions, the location of events vital to the development of Trades Unions and the Labour movement. All three could be described as failures, but the last of these, the great Manningham Mills strike of 1890-91, is still well remembered for it led directly to the founding of the Independent Labour Party.

Two earlier episodes, in 1825 and 1840, were of almost equal importance to the events at Lister’s Mill. I have tried to locate them ‘on the ground’ with contemporary maps from the Bradford Local Studies Library reserve collection. My main source of information has been Bradford Chartism 1838-1840 by A J Peacock (1969, Borthwick Institute). Of course, the city has changed utterly since the mid-nineteenth century and it is not easy for us to place long vanished buildings on modern streets. My intention, in any case, is to use the buildings as a means of examining the aspirations of those who once used them. The Bradford citizens involved in these events deserve much better than oblivion.

Let’s start with worsted stuffs! The last part of the worsted process to be successfully mechanised was wool combing, but in 1824 wool was hand-combed by skilled individuals who were among the highest paid manual workers. In that year a man called John Tester attempted to form a union representing wool combers and, later, weavers. In the following year (1825) he headed a lengthy and bitter strike aiming for better wages and union recognition. The wool combers strike was eventually broken after many months.

The next vital event in the development of Bradford as a wool textile centre was the invention of the power loom. It is generally believed that the first one to be installed in the town was at the premises of JG Horsfall in North Wing in that same year of 1825. The location of this mill can be seen on the first map detail, near the bottom centre. The mill was subsequently attacked by desperate unemployed workers from Fairweather Green. The riot act was read, armed forces fired on the crowd killing two people, and others were arrested. Further episodes of machine breaking followed.

In the 1830s trade unionism existed largely in secrecy but there was a more public campaign for the reform of factory conditions, and Bradford now had an MP. In 1834 the Bradford Political Union was formed which advocated a secret ballot and universal adult male (but not yet female) suffrage. It attracted speakers of the quality of Robert Owen who lectured in the chapel of the ‘Jumping Ranters’ on Bowling Lane (Manchester Road). I haven’t been able to find out much about the Ranters but they seemed to have been an offshoot of the Primitive Methodists. The UK Labour Movement has been described as owing more to methodism than to Marx.

Robert Owen was a Welsh textile manufacturer and social reformer, famous for the industrial village of New Lanark. He formed the Grand National Consolidate Trades Union. Influenced by the GNCTU there were successful strikes by masons and woodworkers in Bradford, men whose skills were in huge demand in a rapidly expanding town.

Peter Bussey had been born in Bedale in 1805. In his life he had undertaken many jobs, including wool combing, before ending up as an inn keeper. He was a voice in every local labour movement throughout the 1830s. At the end of this period Peter Bussey was a publican at the Roebuck Inn.

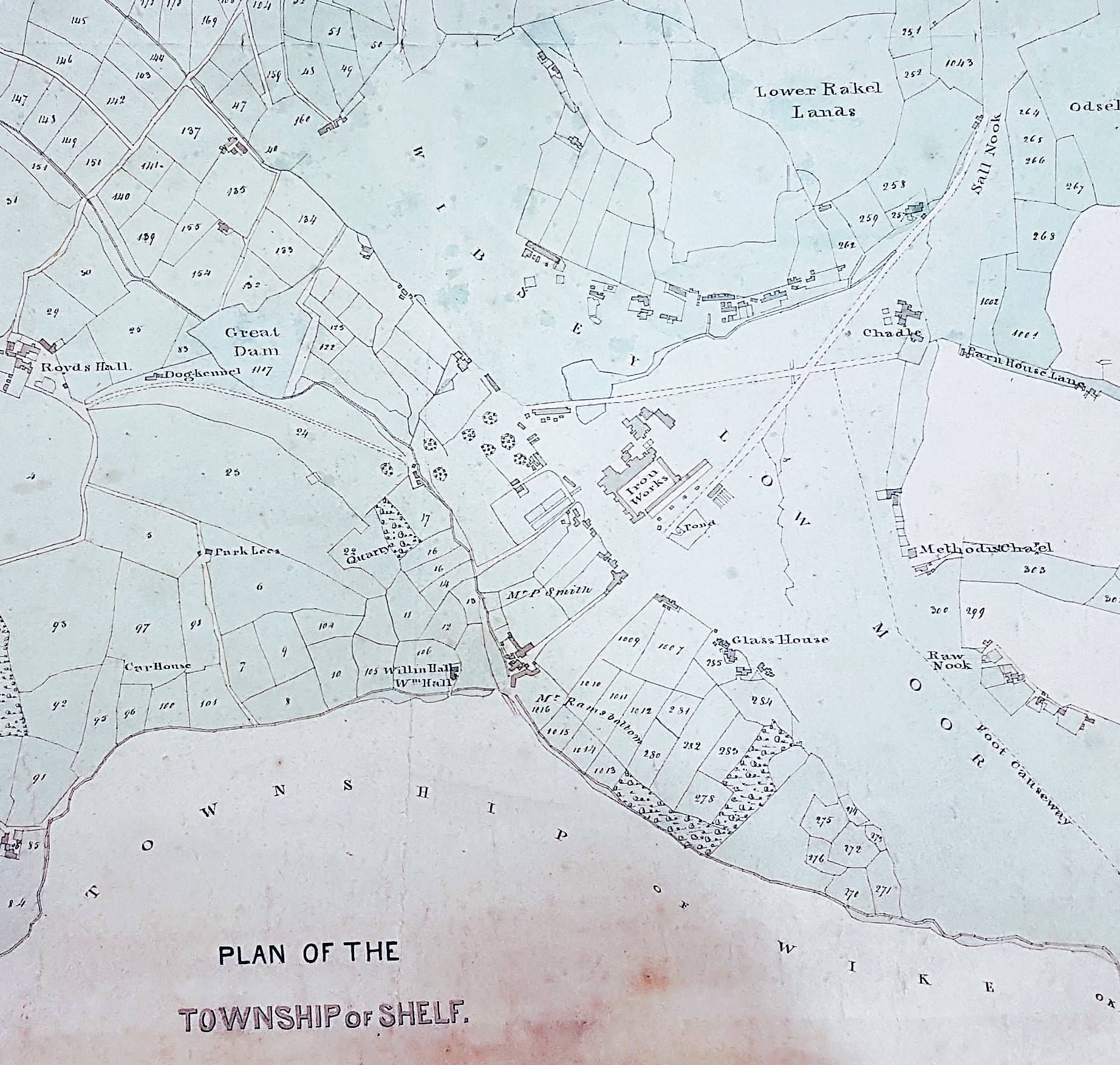

On Wibsey Low Moor in 1834 Bussey addressed a huge public meeting to advance the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs who were convicted and transported for trying to create an agricultural union in Dorset. I don’t know the exact location of the meeting but the plan shows the relationship of Wibsey Low Moor to the Low More Ironworks. Mass protests of this type resulted in a pardon being issued to the martyrs in 1836.

In 1835 Feargus O’Connor effectively became the leader of working-class radicals in England. This highly charismatic orator was at the time out of parliament but was shortly to establish the radical newspaper Northern Star in Leeds and later be imprisoned for his views. In 1835 he spoke in Bradford and founded a Bradford Radical Association, with Peter Bussey as its chair.

In the late 1830s there were also extensive protests against the Poor Law Act 1834, and the setting up of the new Poor Law Unions. These were intended to totally alter the provision of poverty relief, and reduce the costs involved to the government. From that time relief would only be provided from workhouses. The conditions in some workhouses were very harsh indeed. The old 18th century Bradford Workhouse had been set up in Barkerend. Early meetings of Poor Law Guardians in the town were extremely turbulent affairs with troops being needed to escort the new Guardians home. Ultimately a new workhouse was built at the St Luke’s Hospital site and opened in 1851.

There was fierce opposition to the Poor Law act all over northern England. In Bradford Oddfellows Hall was packed to hear Richard Oastler (promotor of child labour reform) and Feargus O’Connor denounce the act, although in the long run the new arrangements were accepted to some degree. They Oddfellows were a secretive friendly society, divided into lodges somewhat like the freemasons. I don’t know a great deal about Oddfellows Hall. The first Ordnance Survey map places it on the town end of Thornton Road, quite near the Soke Mill. John James describes the building as ‘large and substantial’ and costing nearly £3000. It was constructed in 1837. I don’t know if there was any connection with the Odd Fellows Arms, seen in the second plan.

Chartism developed in 1838. It took its name from the Peoples Charter which contained six points: equal electoral districts, universal suffrage, secret ballot, annual elections to parliament, and payment of MPs, who would not in future require a property qualification. Some ‘chartists’ advocated physical force (rather than moral force) as a means of promoting their ideals and Peter Bussey seems to have been one of those. Chartist meetings in Bradford often took place in his pub, the Roebuck Inn, although Primitive Methodist and Methodist New Connection chapels were also employed. Many local chartists were wool combers and weavers, who may well have had memories of the 1825 strike.

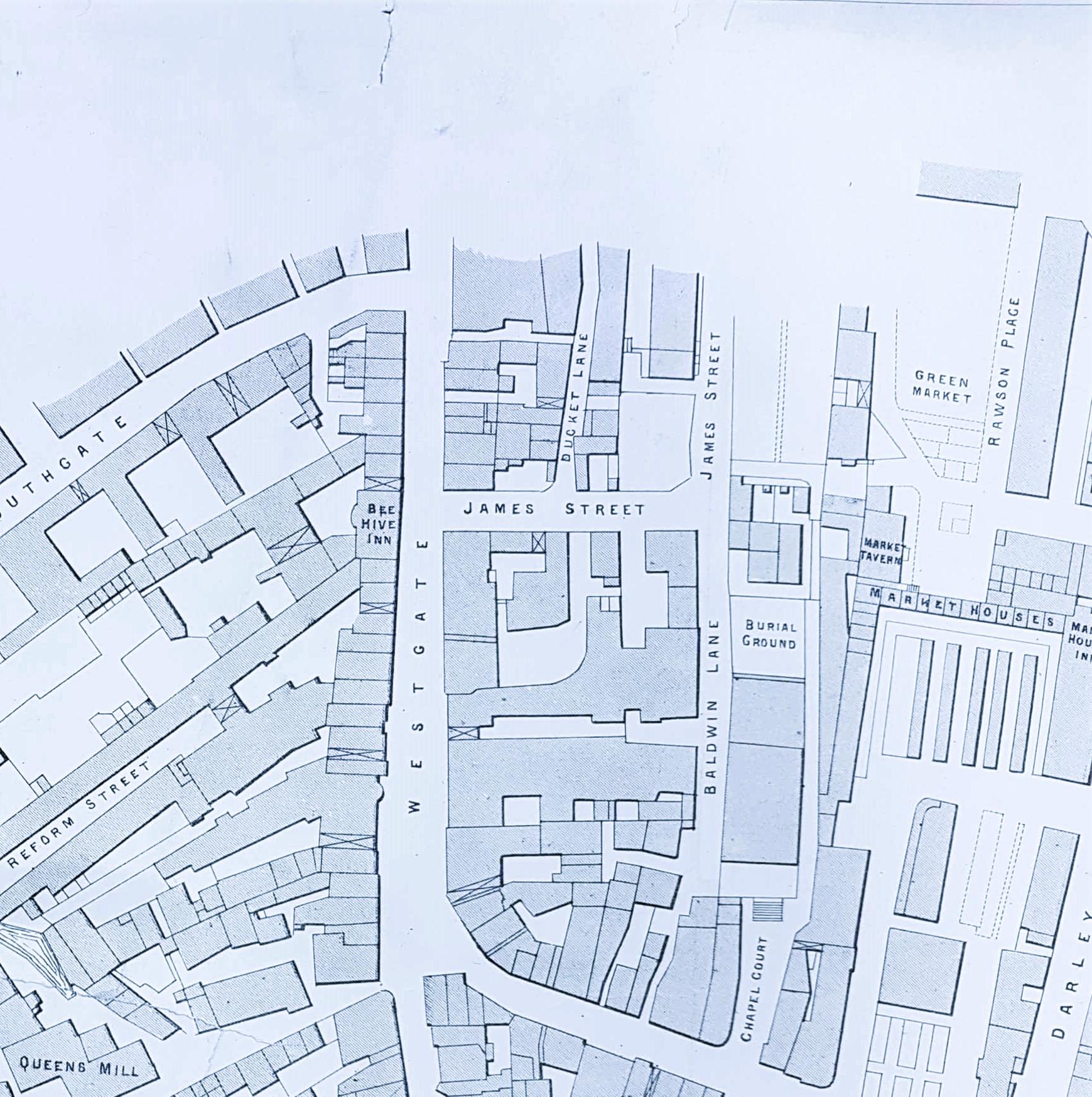

By 1839 Birmingham was the centre of Chartism. Under this name were people of a variety of political opinions, but the movement seemed to be becoming less moderate with a general strike being debated. In Bradford there were rumours of a prospective riot with attacks on mills and millowners’ houses, and as a result a troop of artillery was moved to the town in readiness. Then early in 1840 Peter Bussey suddenly disappeared, presumably because he feared arrest. One night shortly after groups of protesting Chartists moved round Bradford, and one such group seized a watchman in Green Market (top right in the map detail).

In the event the insurrection or ‘rising’, if that’s what it was, soon collapsed. There was very little violence, and several arrests were made. Next day the prisoners were examined in the Bradford Court House, and some were released. The artillery were sent back to its barracks. Nine men were eventually imprisoned for periods of a few years. Were these events an attempt by the Chartists to initiate a national uprising, or had they in some way been fomented by the authorities to identify the more hot-headed Chartist supporters? This is still uncertain.

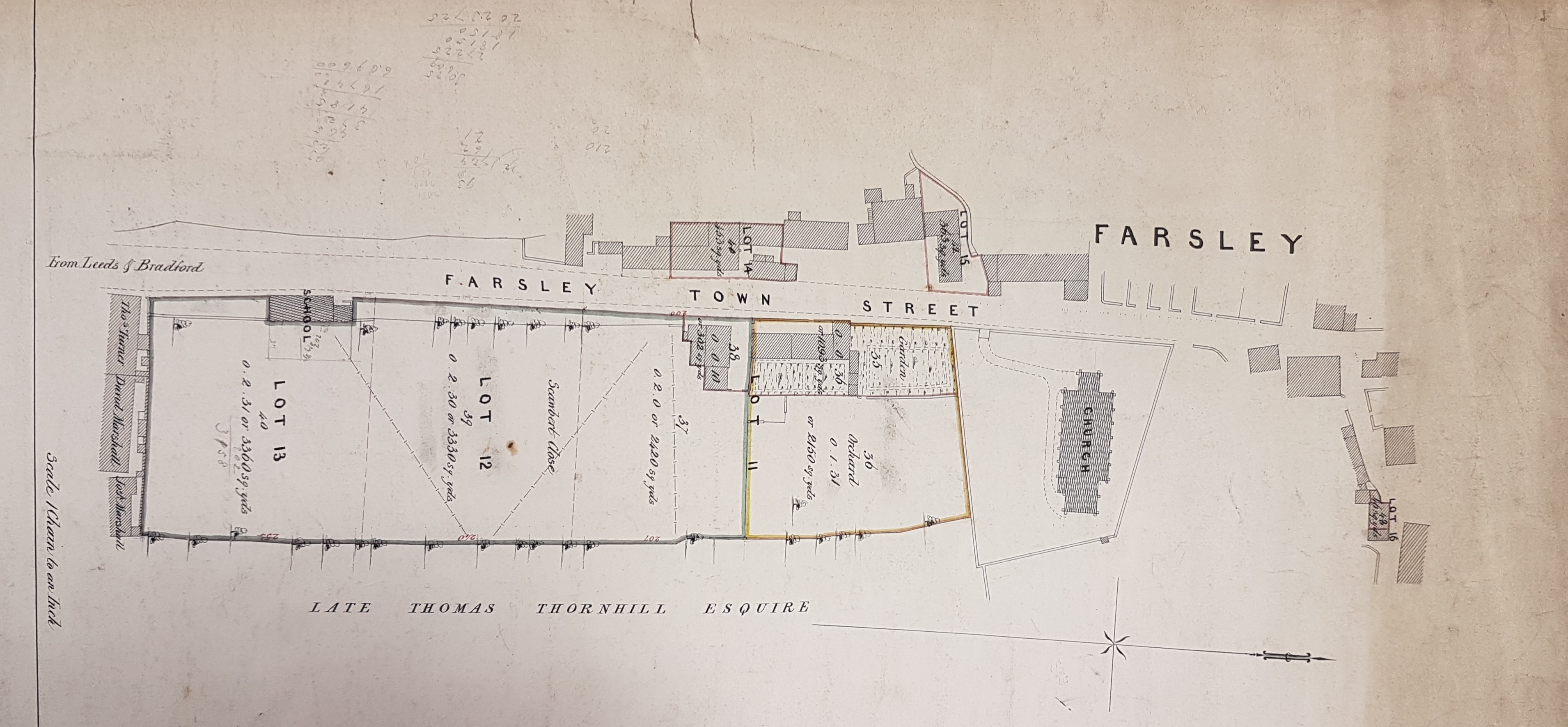

Feargus O’Connor died in 1847. Peter Bussey fled to America and in July 1840 the Roebuck was sold and his family joined him. He was believed to become disappointed with the US political system too, and in 1854 returned to the UK where he lived quietly. He died in 1869 and is buried in Farsley Churchyard. William Scruton described him as ‘violent and extreme’ and a conspicuous figure. But this historian has the justice to admit (writing twenty years after his death) that very few of Bussey’s aspirations had not by then found their way onto the statute book.

Feargus O’Connor actually died in 1855, having led the final phase of Chartism in 1848. In that year there was a great deal of Chartist activity in Bradford which is well worthy of investigation. I wrote my final year thesis on it at Manchester University in 1973.

Thank you for these regular emails. They are invariably interesting and frequently fascinating.

LikeLike