It is perfectly understandably that enthusiasts for old maps wonder if they can be used as a key to unlock a modern landscape. The general answer to this must be ‘yes’ but I have found the process extremely difficult to do in practice, especially in an area of Bradford that is unfamiliar to me. I chose Bowling for a trial since the railway tunnel and track act as fixed markers, and the area (with the adjacent Ripley’s Bowling Dye Works) is very well represented in the Local Studies Library reserve map collection. ‘Ground-truthing’ simply means an exploratory walk and keeping your eyes open. There are two rules though: I shall stick to roads and footpaths, with absolutely no trespassing, and nothing described is beyond the physical capacity of a fit-ish 70-year-old, if care is taken. Safety first at all times!

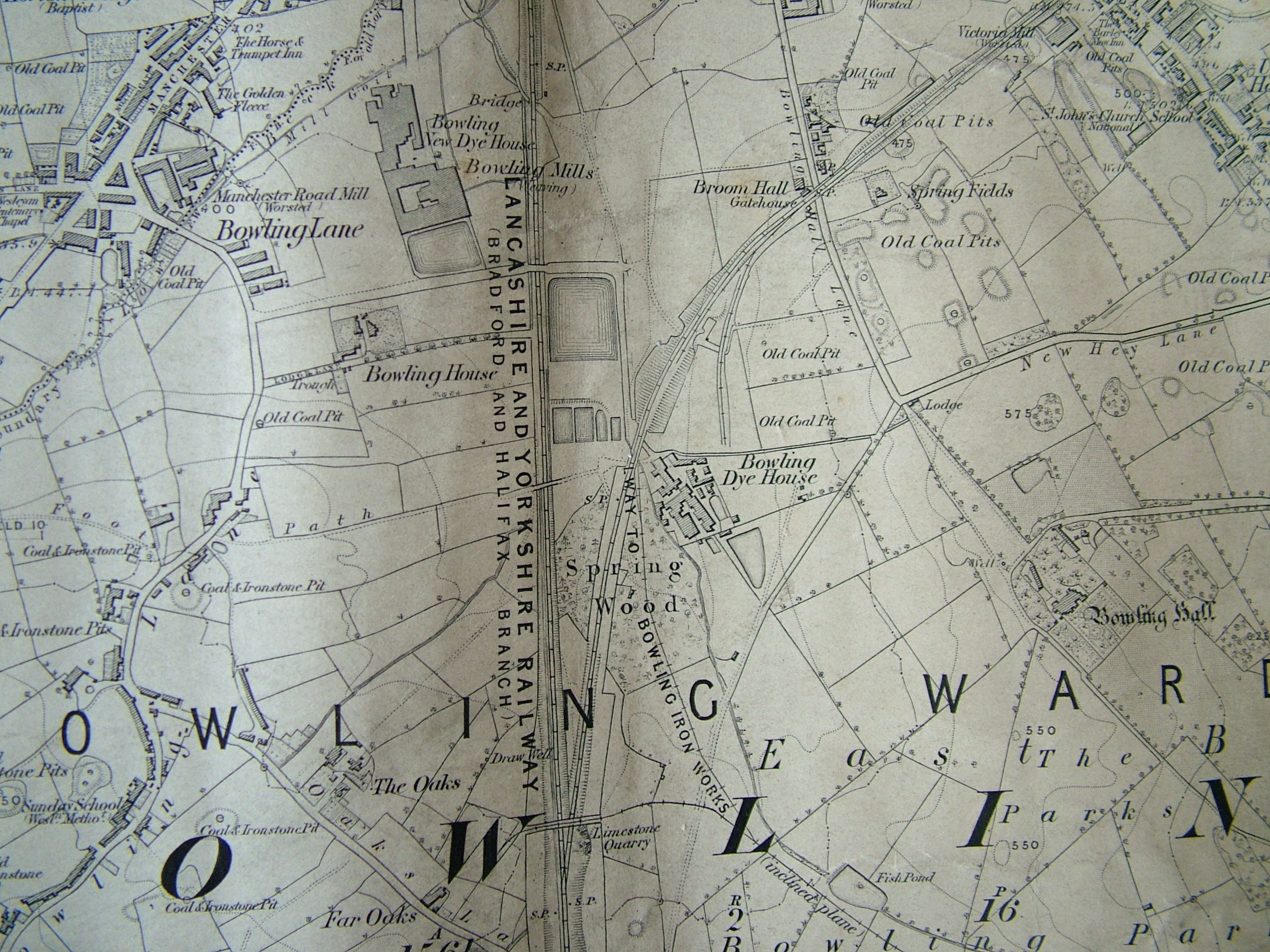

The first image is a detail from the 1852 Ordnance Survey map. It shows Bowling junction, although this is not named. Two, seemingly single, rail tracks, are mapped. The first is the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway line which connected Halifax to Bradford, and its terminus Drake Street (later Exchange) Station, which opened in 1850. The second line moving off to the right went from Bowling junction to Leeds, via Laisterdyke, and was opened a few years later in 1854. It was operated by the same company and, I presume, allowed trains to travel from Leeds to Halifax direct, by-passing Bradford completely.

A ‘limestone quarry’ is indicated. Limestone strata do not reach the surface in the city area but there was nonetheless an early lime-burning industry based on the extraction of boulders from glacial moraines. In this case the digging of a railway cutting presumably exposed the valuable mineral. Plausibly these boulders were taken to the nearby Bowling Iron Company where crushed lime was used as a flux in iron smelting. The ‘railway to Bowling Iron Works’ was a tramway or mineral line along which coal was transported. Note the number of coal pits surveyed. North-east of the junction is Spring Wood. The name has almost certainly nothing whatever to do with a water supply. ‘Spring’ was applied to a tree that had been cut off at ground level for coppicing. Spring Wood was presumably an area of old coppice woodland. William Cudworth records that there was once also a Springwood Coal Pit, but the wood itself soon disappears from maps. ‘The Oaks’ and ‘Far Oaks’ are also reminders of a sylvian past.

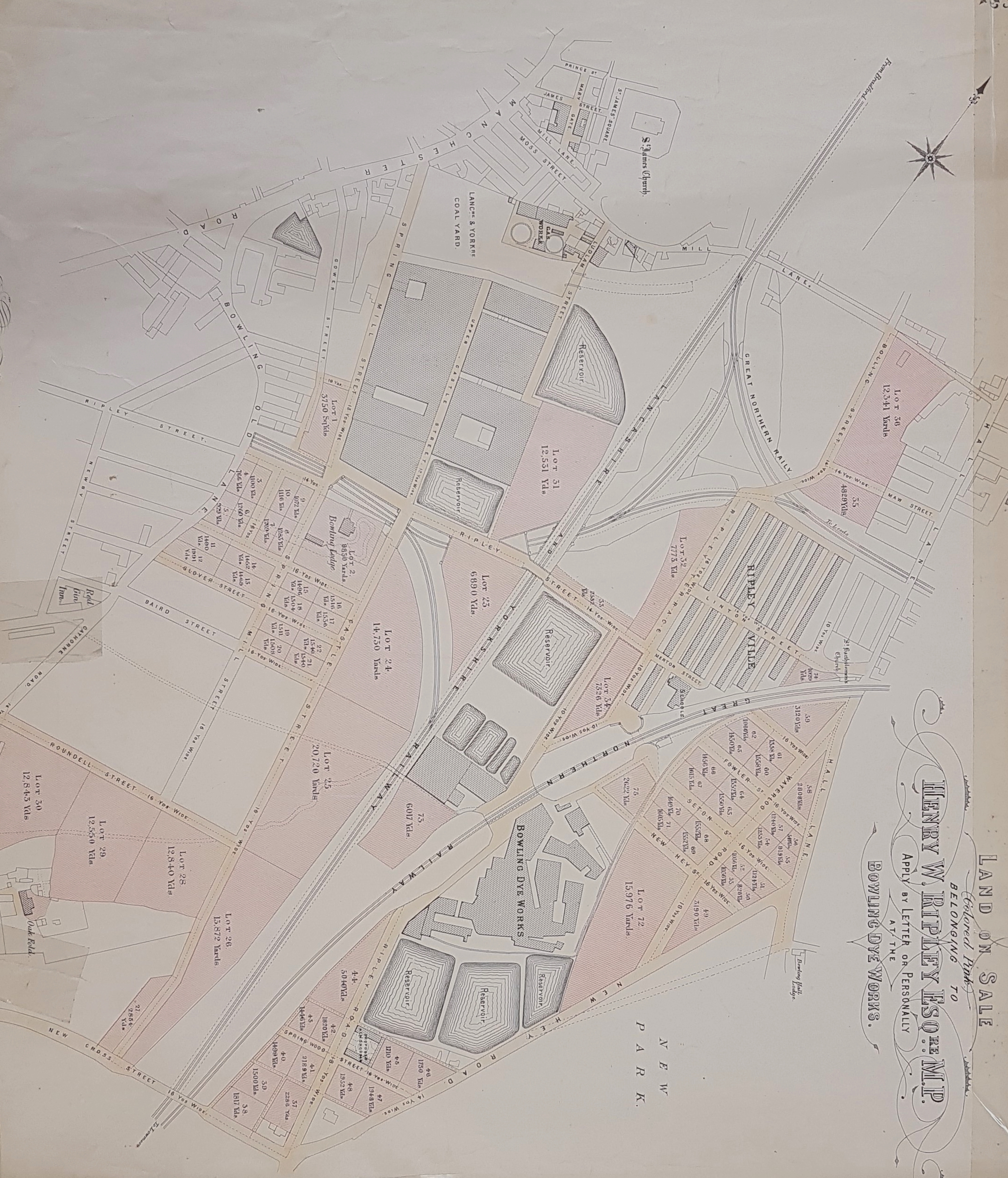

The second map is more useful and should be turned 45 degrees anticlockwise to align it with the OS map. There has been considerable urban development and the arrangement of streets resembles the modern more closely. Henry W Ripley is selling portions of land and must have been alive at the time of the sale. He died in 1882 but the map is at least a few years earlier since he is not using the title of baronet which he received in 1880. The existence of a ‘new park’ isn’t useful as dating evidence since Bowling Park was also opened in 1880. A date of approximately a generation after the OS map would seem reasonable.

What are things like today? I started my walk at New Cross Street bridge. The first disappointment is that the high sides of the bridge don’t permit the observation of the railway tracks. Once you have crossed the bridge on the left are a fine set of alms-houses, where lot 38 is located. The datestones indicate (in Roman numerals) rebuilding in 1881.

After this success things start to get difficult: Ripley Street is truncated by a huge works, although aerial photography suggests that one of the three reservoirs here has survived. This section of ‘New Hey Road’ on the map is now called Bowling Park Drive. The park is on your left: to the right the dye works and the streets to the north of it have vanished and the site is covered by industrial development. On the ground you can progress a little further north than the mapped park lodge and Hall Lane and then, just before you reach the junction between Bowling Park Drive and Bowling Hall Road, there is a mysterious flight of steps to the left.

Take care if you descend since there is no hand-rail. The steps lead to a footpath paved with stone setts. The path is present on the OS map, running east-west immediately above the words ‘Bowling Dye Works’. At the bottom of this path are very high stone walls which I assume were once the perimeter wall of the works. Finally, you reach the curve of the Great Northern track from Bowling Junction to Laisterdyke. The track no longer exists but the line is visible on aerial photographs such as those provided by Google Earth. I assume the line was on the embankment now covered in trees. A right turn is blocked by security fencing but a left turn takes you along a paved footpath which shortly joins another section of Ripley Road.

You can continue along this road to Ripley Street. North-east of this point was once the development known as Ripleyville. After 1863-64 Ripleyville, consisted of 200 houses with schools, was constructed by Sir Henry in a conception similar to that of Saltaire: sadly nothing now remains. Turning left takes you across a railway bridge from which the lines are visible.

Once across the bridge take the second left along (Upper) Castle Street which features on the second map and takes you back to New Cross Street with its impenetrable bridge. This is the further of the two bridges you can see on this image.

So how much is left on the ground since the second map drawn about 150 years ago? Very little must be the answer.

Will you be going to bowling cemetery, it is somewhere there are probably swaines.

LikeLike

perhaps they sold his land off 1880 to pay for almhouses and other matters they were interested in and he died in 1882. I wonder who lived in the almshouses? Linda Drew

LikeLike