10.005 BRA c1820 CAN

Size: 125*75 cm Material: paper

Scale: 1.5 chains per inch Condition: fair

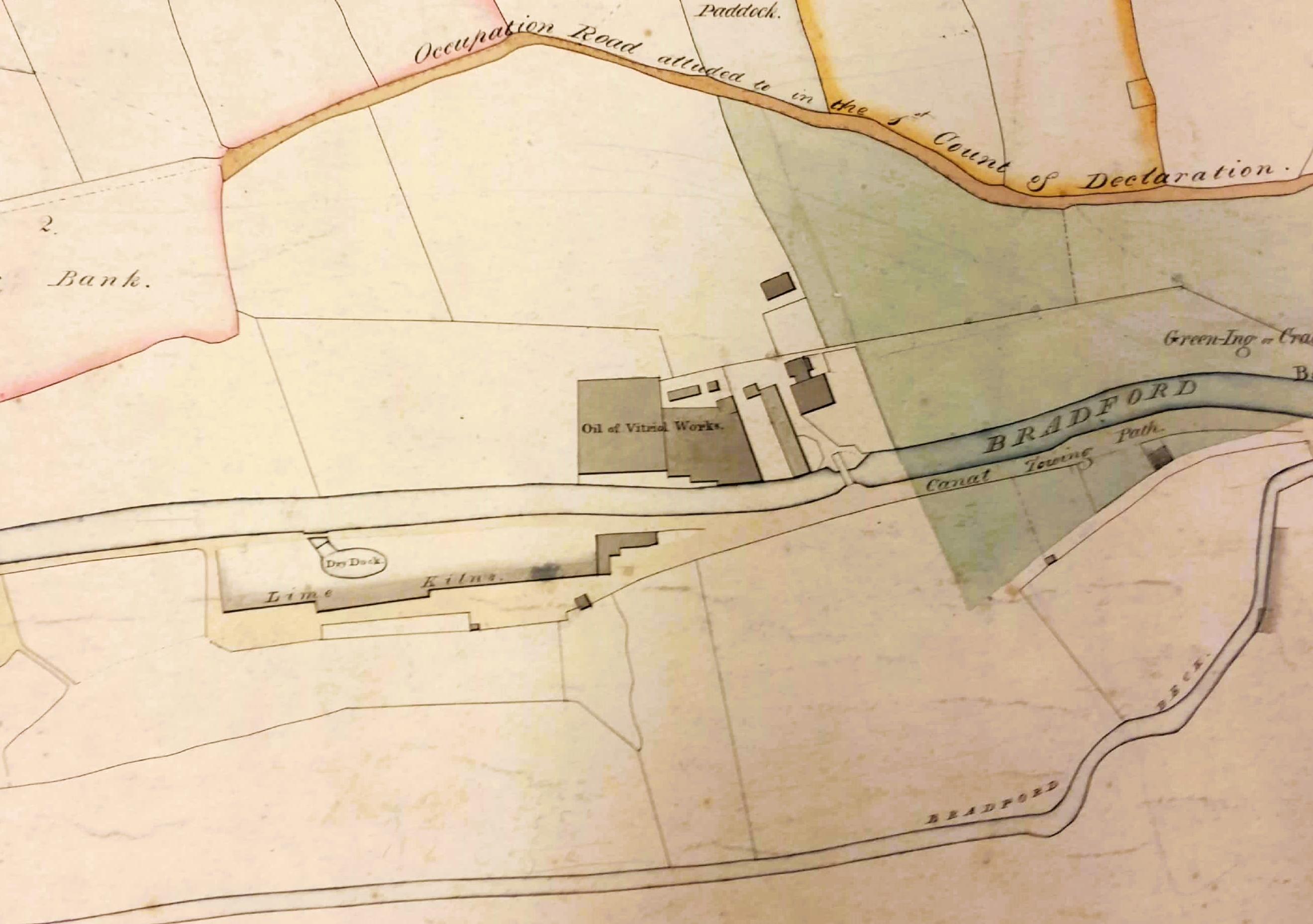

The first plan seems to originate in a legal dispute, Thornton & Others against Pollard. This is the defendant’s plan. The defendant is Pollard who, I take it, is involved with the Bradford Canal Company in some way. The point at issue seems to be a right of way between Broad Stones and Bailey Croft Bridge on land owned by the company. The plan is undated but use and ownership dates between 1791 & 1819 are indicated. The value of this plan to us doesn’t depend on understanding the legal niceties but resides in the very precise surveying of land and property between Spinkwell Lock and the Canal Basin about 30 years before the first Ordnance Survey map.

This detail is immediately west of the first. Firstly, note the ‘Oil of Vitriol’ works. In 1746 John Roebuck (Birmingham) had adapted a process of burning sulphur with saltpetre to form sulphur trioxide, within acid-resistant chambers made of lead. Sulphur trioxide was then dissolved in water to form the vitriol. The acid would attack all eighteenth century known metals except lead and gold. Lead was chosen for the chambers since it was the cheapest acid-resistant metal available but please, please, do not try this conversion at home.

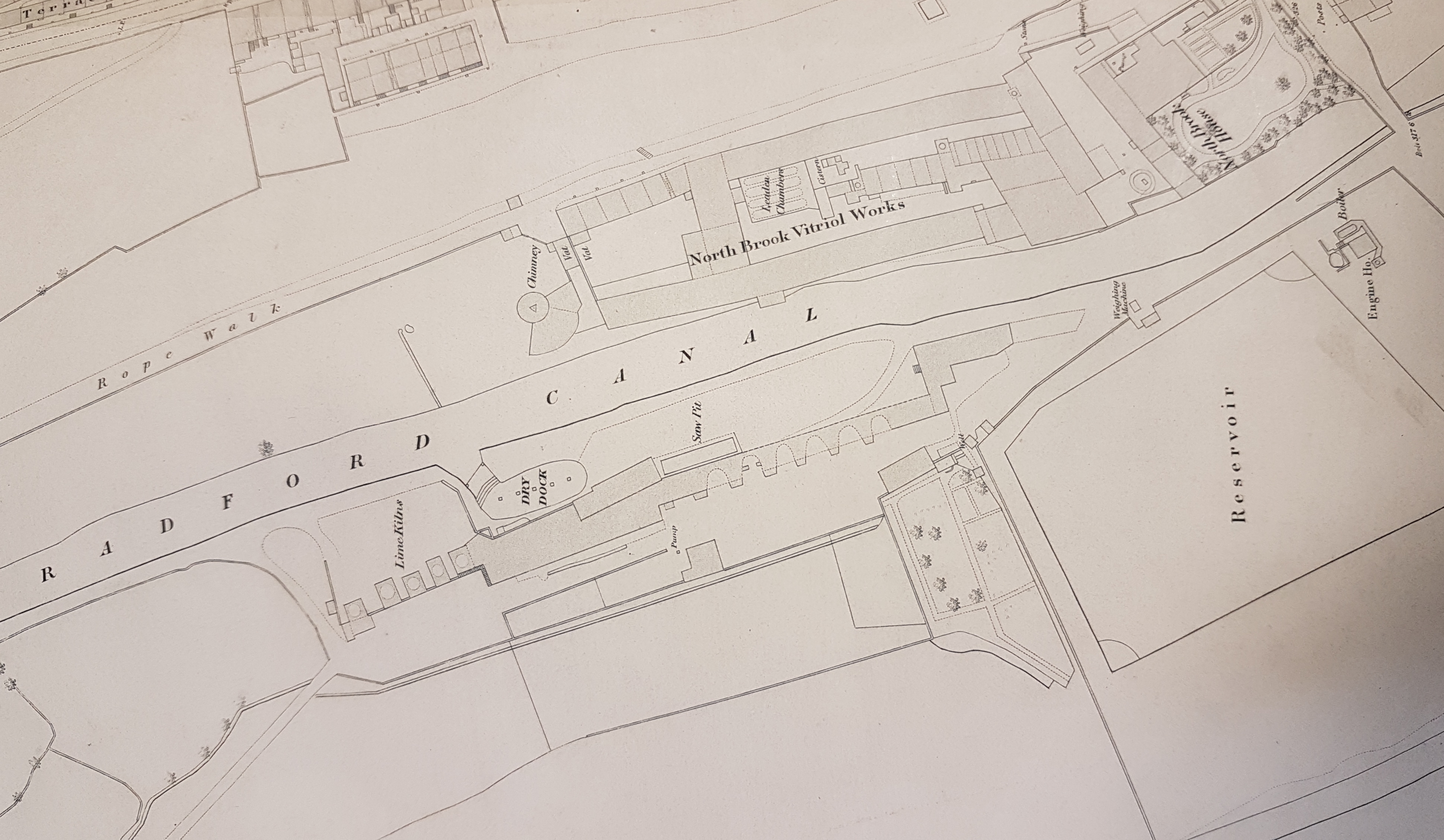

North Brook Vitriol Works was situated between Wharf Street and Canal Road. Vitriol and aquafortis (nitric acid) were first made there by Benjamin Rawson (1758-1844). The works is believed to have been in operation by 1792 which makes it one of Britain’s first chemical plants. In this and much else Bradford was ahead of the game. Shortly afterwards Rawson purchased the Lordship of the Manor of Bradford, a role in which he and his two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, will be familiar to local historians. In 1838, before Rawson’s death, the works were bought by Samuel Broadbent. He lived in Northbrook House and his garden led to the canal. Additional chemicals were now made such as spirits of salts (hydrochloric acid) and ammonia.

Below the vitriol works are a canal-side bank of limekilns. The second map detail shows these in much greater depth, as well as the position of the lead chambers. Very unfortunately I can’t yet track down the original map that I photographed to provide this information. It was assumed that, like coal, limestone would be one of the main cargoes carried on the canal. The material was burned or ‘calcined’ to provide quick lime which could be slaked with water. The product was spread on the land to neutralise acid soils or used to make mortar. The iron works in Bradford also required limestone to mix with coke and ironstone in the blast furnace smelting process.

There are several other points of interest in the second map. Between the canal and the kilns is a ‘saw pit’. I assume timbers were cut here using a double handed saw managed by a ‘top-dog’ and a ‘bottom-dog’. The resulting planks might well have been used to repair canal boats housed in the nearby dry dock. I assume that the cables produced in the ‘rope walk’ behind the vitriol works were used by the horses to pull the boats. I assume the second plan is older than the first since a large reservoir has evidently now been dug east of the kilns. This is present on the first Ordnance Survey map of the area which was being surveyed in the late 1840s, and I believe it was part of North Brook Mills.

When was this mill constructed? Later plans seem to show the integrated premises of a worsted manufacturer who has a spinning mill and a weaving shed, both with their own steam power. A substantial warehouse is included, presumably both for raw wool and finished cloth. There is no dye-works and so, as was common practice, woven stuffs must have been sent to commission dyers. The name associated with North Brook Mills is William Rouse snr. (1765-1843). He was a significant name in the Bradford textile history. He developed a wool combing factory in the years before this process was mechanised. With his son John (1794-1838) he employed hundreds of hand combers who worked for him producing the wool ‘tops’ that were needed for worsted cloth. By the time of William’s death the writing was on the wall for the poorly paid hand combers whose trade was effectively destroyed by mechanical wool combs in the 1850s. It is known that the business continued despite the deaths of William and John. The 1853 White’s Leeds & the Clothing District Directory does does mention a William Rouse, spinner & manufacturer, of West Lodge, Great Horton Road. His company is Wm. Rouse & Sons, Old Market & Canal Road. So there clearly was a William Rouse jnr. (1809-1868) who succeeded his father. In the 1851 census Rouse reported employing 400 combers, 100 boys & 150 girls. William Rouse jnr. did everything expected of a successful textile man: church warden 1847, town counsellor 1848, magistrate 1852, and Poor Law overseer 1860. By 1861 he was living in Burley House, Burley with his wife, children, and six servants. He died in 1868.