The world recognises Bradford as a textile city, but five important industries preceded spinning and weaving. These were: stone quarrying, coal-mining, iron-smelting, brick-making and chemicals. There was even dalliance with two others: pottery at Eccleshill and Wibsey, and glass-making near Low Moor. I think is fair to say that, to a substantial degree, these once vital activities are neglected or even forgotten. I don’t know of a comprehensive modern account of the whole of Bradford industry, although individual groups in (for example) Low Moor, Thornton, Heaton, Baildon and Eccleshill have learned much concerning their own immediate areas. For the interested student, there are excellent resources in the Local Studies Library and West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford), and also at the Bradford Industrial Museum. Useful accounts of aspects of the city’s industrial past can be found in the pages of the Bradford Antiquary; copies of which journal can be found in the LSL.

On this occasion I will not be describing a single map but trying to illustrate something of the history of local coal mining, with maps from the reserve collection that have previously been displayed individually. If I manage to interest you then why not see if you have some talent as a landscape archaeologist? I promise you that a visit to Judy Woods, Heaton Woods, Northcliffe Woods or Baildon Moor will display evidence of mining and other industries all around, softened by the effects of a century or two of nature’s return! The interested, library-based, student should start with the 1802 map of Bradford which is in the public collection at the LSL. It shows absolutely no signs of coal mining whatsoever. It may be that mining was more prominent in surrounding areas (being established by the seventeenth century, if not earlier, in Heaton, Baildon and Eccleshill) but the land on which Little Germany was constructed, the property of the ubiquitous Rev. Godfrey Wright, had previously been known as ‘Collier’s Close’.

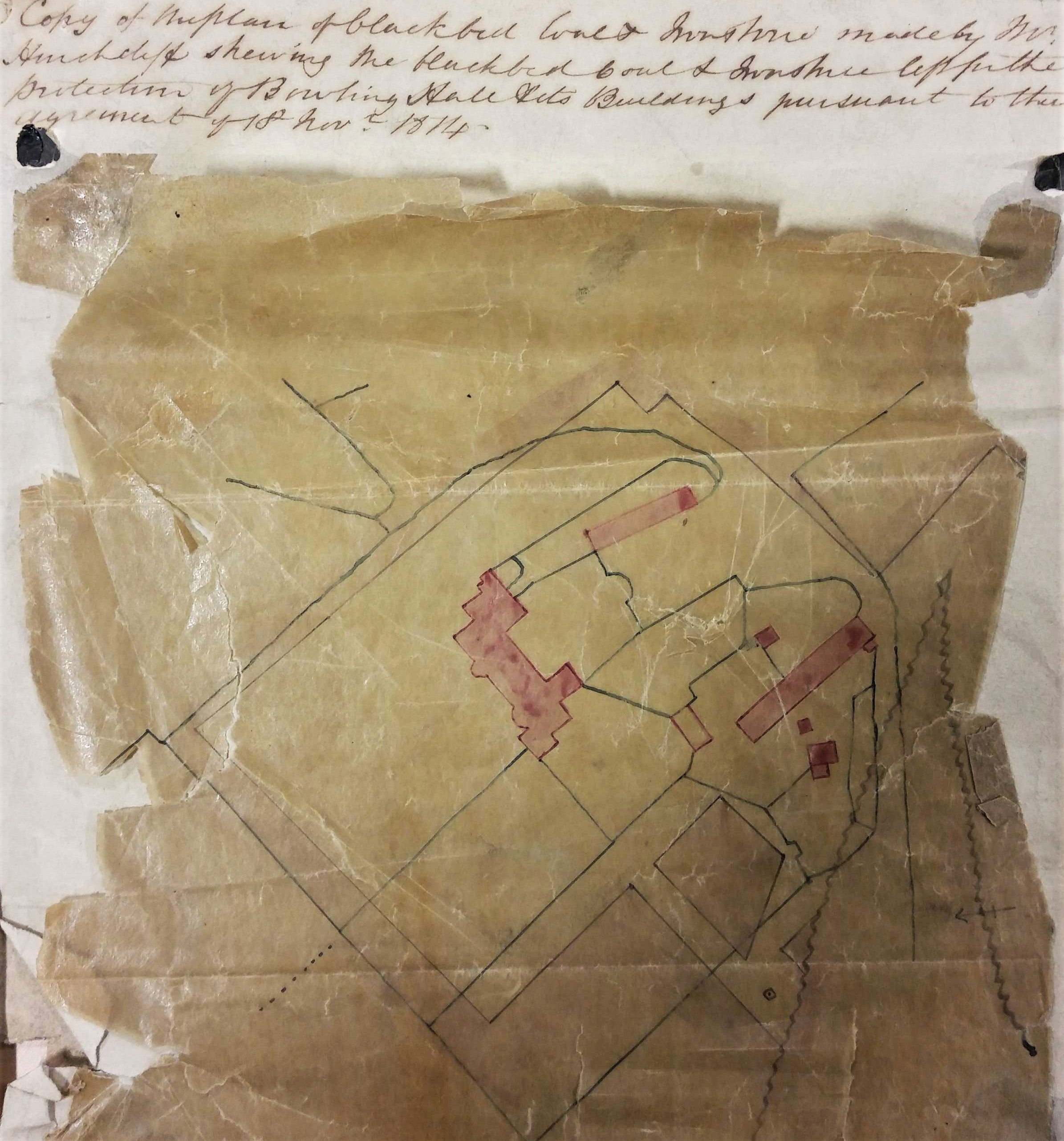

Victorian hand-writing is not always easy to read but, with small adjustments to spelling and capitalisation, the first plan is headed: ‘Copy of the plan of Black Bed coal and ironstone made by Mr Hinchcliffe showing the Black Bed coal left for the protection of Bolling Hall and its buildings pursuant to the agreement of 18th November 1814‘. In this fragile plan pink blocks represent Bolling Hall and its out-buildings. Many of the black lines are property and field boundaries. This whole central area is slightly paler in colour than the region outside the precinct boundary, which is darker and I assume represents winnable coal. The wavy line, in an inverted V shape to the right, is a geological fault. In his description of the area historian William Cudworth reported a Bolling Hall fault which threw minerals ‘down 28 yards to the south’. The coal mining concession was held by the Bowling Iron Company from the landowner, Sir Francis Lindley Wood. BIC had been established in 1780. It smelted iron ore found in the roof of the Black Bed coal seam, both of these minerals being mentioned in the plan rubric. A deeper coal seam, the Better Bed, made sulphur and phosphorous-free coke, which was ideal for iron smelting. This seam is not mentioned on this plan, nor is the shallower Crow Coal. The removal of the Black Bed and its ironstone naturally left a gap into which the overburden of rock could collapse, resulting in surface subsidence. The common practice was to leave pillars of minerals unmined to support the roof. Under especially sensitive areas, which included churches and the mine-owner’s house, no mining at all took place. To indicate such restraint must be the purpose of this plan which is now transferred to the WYA.

The pattern created by the ‘new roads’ portrayed on the second map exist on the Bradford plan of 1830, so we are probably looking at a map from the late 1820s. A coal staithe is a place adjacent to a highway from which merchants can collect a supply for subsequent delivery to their customers. The obvious staithe here is marked J.S. & Co. Clearly this represents John Sturges (or Sturgess) & Co. which was the company that operated Bowling Iron Works. The ‘new rail road’ drawn is in fact a mineral carrying tramway bringing coal in trucks to the Eastbrook staithe, by rope haulage, from the iron works. Bowling Iron Company owned and operated many collieries and ironstone mines. The trucks may have been returned filled with limestone, needed for iron smelting, which would have arrived at the nearby canal basin from the quarries at Skipton. The tramway was closed in 1846 and the area is marked as an ‘old staithe’ in the first OS map of the area. The is a second staithe on this map which in turn was operated by the Low Moor Iron company: can you locate it?

Mining in Wilsden is well recorded by maps held by both West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) and the LSL. The Archives has a plan (WYB346 1222 B16) of Old Allen Common in Wilsden including its collieries. This shows the area where Edward Ferrand Esq, as Lord of the Manor, had mineral rights over common land. This was ‘made for the purpose of ascertaining the best method of leasing the coal’ by Joseph Fox, surveyor, in 1829. The collieries named were operated by Padgett & Whalley, and Messrs. Horsfall. The LSL has two Wilsden colliery plans. The first shows the Norr Hill drift mine at which the deeper Soft Bed was accessed down an inclined plane. The third image here illustrates mines at Old Allen Common and Pudding Hill which were of the more common shaft mine type. The Soft Bed seam was accessed by the Jack Pit and Jer Pit. Tom Pit accessed the shallower Hard Bed seam. There is a system of galleries, and again evidence of faulting is marked. One gallery heads towards Padgett’s Colliery. Many areas are ‘old’ or worked out.

Mines like these would need to be drained and ventilated. Drainage was often achieved by digging a long underground channel or ‘sough’ to take water to a lower level surface watercourse. As well a shaft to access the galleries a second ‘air’ or ventilation shaft was often sunk. In operation active men were needed as ‘getters’ to hew the coal. As the seams were thin this must have been undertaken in a lying or kneeling position illuminated only by flickering candlelight. Hewed coal was then conveyed in wicker baskets, called corves, by ‘hurriers’ to the shaft bottom. If they were physically capable children and women could fulfil this function, although women working underground were seemingly becoming rare in the Bradford area by the early nineteenth century. The full corves of coal could be extracted by a hand-windless or, if the shaft were deep, a horse gin, and then removed by carts or packhorses to the nearest roadway.

By the time of the 1852 Ordnance Survey map there was a large colliery just south of Miry Shay called Bunkers Hill. The land ownership in this area is made clearer by this last map which also illustrates that the name Bunkers Hill was in fact applied to a series of collieries along Barkerend Road. The ‘Col. Smyth’ in this map is John George Smyth (1815-1869) MP for York and Colonel of the 2nd West Yorkshire Militia who lived at Heath Hall, Wakefield. His land holdings north of Barkerend Road are now a substantial part of Bradford Moor Golf Club. Adjacent was the Boldshay (Boldshaw) Hall Estate. Boldshay Hall, Barkerend was built c.1740 and at this early period was associated with the name of Samuel Hemingway and his son Henry Hemingway, who were both lawyers. The estate itself is presumed to be far older. Remarkably the hall still exists on Byron Street, surrounded by Victorian housing, and is Grade II listed. The gardens, fields, and coal mines which once enclosed it have long ago vanished completely.

To people labouring as miners in the early nineteenth century the industry must have seemed timeless. Could they ever have imagined that in 2015, with the closure of Kellingley Colliery, the deep-mining of coal in Britain would be brought to an end?