Although I have used maps of locations in Bowling for various Local Studies Library blogs, and earlier Maps of the Week, I don’t feel I completely understand how the various sites once fitted together, interacted, and evolved over time. It follows that I am more anxious than usual to hear from anyone who knows the story of the area particularly well. There are several difficulties placed in the way of the student of this community’s history. Today the spelling ‘Bowling’ is used for the district, and the alternative ‘Bolling’ for the hall, and the family who once owned it. In the past writers were not always so discriminating. Several modern accounts of the area seem to depend very heavily on the writings of the noted Bradford historian William Cudworth. While this is perfectly understandable I should like, in what follows, to use maps and plans to augment our knowledge to some degree. The LSL has a number of maps relating to the ancient Township of Bowling, in both its main and reserve collections, but I have also employed material from Bradford Industrial Museum and the West Yorkshire Archives. Finally there are three very important historic sites in Bowling: moving from west to east we have the Bowling Dyeworks, Bolling Hall, and the Bowling Ironworks. It so happens that they are all in the north of the township and I am much less clear about the situation in the south, especially that portion of ‘traditional’ Bowling extending south of Rooley Lane.

The first image is a detail from the 1852 Ordnance Survey map. It shows the first two of the three sites together with Bowling Railway Junction, although this is not named. The Bowling Iron Works is off the top right of the map. There are two rail tracks mapped. The first is the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway line connecting Halifax to Bradford, and its terminus Drake Street (later Exchange) Station which opened in 1850. The second line, moving off to the right, went from Bowling junction to Leeds, via Laisterdyke, and was opened a few years later in 1854. It was operated by the same company and, I presume, allowed trains to travel from Leeds to Halifax direct, by-passing Bradford completely. The track no longer exists but the line is visible on aerial photographs. The third loop line which connected Exchange Station to Leeds via Laisterdyke has not yet been constructed. At Bowling Junction a ‘limestone quarry’ is mapped. Limestone strata do not reach the surface in the city area but there was nonetheless an early lime-burning industry based on the extraction of boulders from glacial moraines. Boulder pits were certainly established in Bingley by the early seventeenth century. It looks as if glacial erratic limestone boulders were found elsewhere and were being exploited in the same way. Plausibly these boulders were taken to the nearby Bowling Iron Company, just off the right edge of the map, where crushed lime was used as a flux in iron smelting. There is plenty of indications of old coal mining throughout the area. Spring Wood is located near the dye works. The name has almost certainly nothing whatever to do with a water supply. A ‘spring’ was a tree that had been cut off at ground level for coppicing. William Cudworth records that there was once also a Springwood Coal Pit, but the wood itself soon disappears from maps.

What are the margins of the Bowling township? The Law Beck formed the traditional western boundary with Horton. Since it became invisible Manchester Road (a turnpike since 1740) is an approximate equivalent. Rooley Lane and Sticker Lane (part of a turnpike since 1734) are roughly the southern and eastern boundaries, if you are prepared to ignore the traditional more southerly triangular area including Odsal Wood. The northern boundary is along Bowling Back Lane: Bowling doesn’t extend as far north as the East Brook and didn’t include the Birks Hall Colliery adjacent to the lane and the iron works. As an additional complexity Bowling was divided into West (Little) and East (Great) divisions, along the line of the Bowling Beck, although I think you would be puzzled to find this watercourse today. This division places the Dyeworks in West Bowling and the Hall and Ironworks in the East but I don’t see that this distinction has much practical value today.

The second sale map shows Bowling Dyeworks in its developed state in the 1870s. Cudworth reports that the works was started by George Ripley around 1804. The Bowling Dye Works and the Bowling New Dye House were both parts of Edward Ripley & Co. which was the name of George’s son. By the time of this map the third loop line connecting Exchange Station to Leeds has been built. The large reservoir and dye pits are a prominent feature in the OS map and the above example. When were these created? The Bradford Observer reports a large sale of land in this area, including that piece accommodating the Dye Works, in 1850. The vendor isn’t stated but might well be the Bowling Iron Company. After 1863-64 Ripleyville, consisting of 200 workers’ houses with schools, was constructed by the founder’s grandson, the famous Sir William Henry Ripley (died 1882) although little of this now remains. Probably the dye works head purchased land at this time to allow for the expansion of his business and the assurance of adequate soft water supplies, which included a reservoir. Cudworth records a 100 acre purchase by the Ripley company and also states that a contractor called Samuel Pearson constructed reservoirs for Bowling Dye Works and Bowling Iron Works at a date ‘early in the fifties’. Samuel Pearson was a Cleckheaton brick-maker who founded a contracting dynasty. His nearby, but largely forgotten, brick works in Bradford was known as the Broomfield Clay works, later the Sanitary Tube & Brick Works. The works is not shown on the second map but was situated inside the GNR loop line adjacent to St Dunstan’s Station, north-west of Ripleyville in the empty space between Mill Lane and Bolling Street. In describing the work involved in taking the railway line from the Exchange Station towards Leeds in 1866 Horace Hird (Bradford in History, 1968) mentions the activities of Pearson & Son who took over responsibility for the material excavated from the cutting. They created a ‘great mound’ and for 15 years 60 men were employed making drain pipes, chimney pots and bricks from this clay debris. Samuel Pearson died in 1884 (worth £20,000) but the company was turned into an international contracting concern by his grandson Weetman Pearson (later the first Lord Cowdrey).

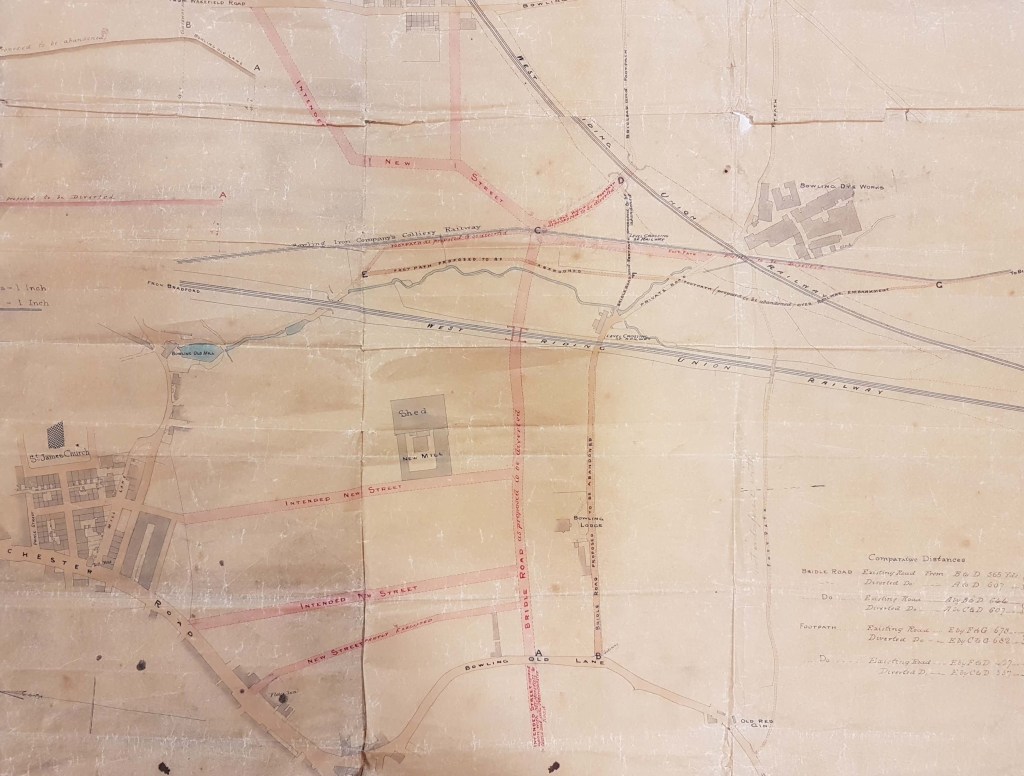

The LSL does have an earlier plan of the area from the 1850s. It centres on intended new streets east of Manchester Road and Bowling Back Lane and also a new mill shed which became part of Ripley’s Dye Works. The plan clearly pre-dates the 1871 Bradford map and the 1852 OS map of the area, but the Dye Works and the earlier two railway tracks are present. The most obvious features ‘missing’ from this plan are the reservoir and dye pits which were sited between the two tracks, adjacent to the Dye Works itself. The Old Red Gin (bottom right) was a public house and a nearby colliery had the same name. The ‘gin’ was probably not the spirit but a contraction of ‘engine’, the means by which coal and colliers were removed from a colliery shaft.

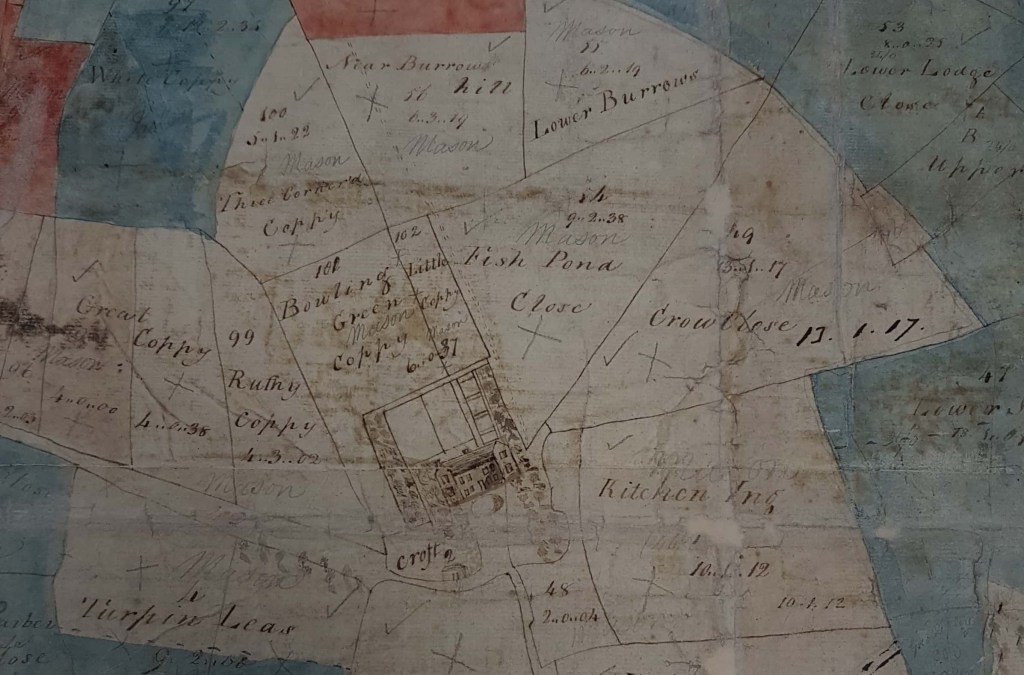

Bolling Hall is a Grade 1 listed building open to the public as a museum. Along with the cathedral, it must represent the city’s premier historical site. The plan shown is a detail from a beautiful Bolling Hall Estate Map (94D85/16/6/1) which is curated by the West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford). It is obvious that some of the fields have been coloured red or blue at a later date, and the names Mason, Sturges and Paley have been added in pencil. The names are those of the original Bowling Iron Company partners and the division of the estate among these men is likely to have occurred when it passed into the ownership of BIC in 1816. The hall and its immediate surrounds carry the name of Mason. At first sight the small picture of Bolling Hall does not look very accurate but we have to remember that the present entrance is via the medieval tower at the rear but the map illustration shows the front elevation. The medieval tower is concealed. The Georgian bay at the left of the building seems to be present and was constructed in 1779-80. Towards the end of the 18th century the owner of the Bolling Hall estate was Captain Sir Charles Wood RN, a painting of whom is still displayed on the main staircase. Captain Wood died of wounds and was succeeded as land-owner and baronet by his son Sir Francis Lindley Wood (1771-1846). Both as estate owner and Lord of the Manor of Bowling Sir Francis controlled access to an immensely profitable asset, the sub-surface minerals. In 1794 Sir Francis gave the BIC permission to mine coal and iron ore under his whole estate. After five years he evidently grew tired of being surrounded by mines and spoil tips, however rich they made him, and moved to another of his houses, Hemsworth Hall near Barnsley. I hope he didn’t anticipate a coal-free zone there.

This is my favourite plan found in the Local Studies Library reserve collection. It is 200 years old and is highly relevant to the history of the Bolling Hall estate at a date immediately before it was sold outright to BIC. Victorian hand-writing is not always easy but, with small adjustments to spelling and capitalisation, it reads: ‘Copy of the plan of Black Bed coal and ironstone made by Mr Hinchcliffe showing the Black Bed coal left for the protection of Bolling Hall and its buildings pursuant to the agreement of 18th November 1814‘. Pink blocks represent Bolling Hall and its attendant out-buildings. Many of the black lines are property and field boundaries. This whole central area is slightly paler in colour than the region outside the precinct boundary, which is darker and I assume represents winnable coal. The wavy line, in an inverted V shape to the right, is a geological fault. Essentially the plan enshrines the old principle that you didn’t mine coal under churches and the mine-owner’s house!

At present I cannot find a good map of Bowling Iron Works in the LSL collection. I have decided to represent it with an illustration from a thesis written by Derek Pickles on the tramways and mineral lines that supplied the works. The founding partners of Bowling Iron Co. in 1788 were: John Sturges (elder) Sandal, John Sturges (younger) Leeds, William Sturges (Datchet), Richard Paley (Leeds) and John Elwell (Wakefield). Cudworth describes the works as being situated in deep horse-shoe shaped valley. The earliest buildings constructed on valley floor but later expanded over the surrounding spoil-heaps. Cupola furnaces were ‘charged’ from the valley side and molten metal was channelled to a foundry on site. There were machine and hammer shops. The buildings on valley floor were surrounded by a high wall: this, and the buildings, were made of hand-made bricks produced by Bowling Iron Works itself. The local coal seams are the ‘Black Bed’ and ‘Better Bed’ coal. The iron ore was a roof stone in the Black Bed seam: the Better Bed made high quality coking coal largely free of sulphur and phosphorus which was ideal for iron smelting. The Bolling (and also the Low Moor) Iron companies exploited the same seams of coal and iron ore over the whole of south Bradford and the surrounding areas. Huge networks of tramways and mineral ways grew up to bring the precious substances to the coke ovens and blast furnaces. Derek Pickles made a very detailed study of this network and its associated mines, in the 1970s I would surmise. A copy of his thesis is now curated by Bradford Industrial Museum. I know nothing more about the author although he did write to the Bradford Telegraph & Argus as recently as 2006.

Coal supplies were transported to staithes in the town centre as this map from the early nineteenth century shows. A coal staithe is a place adjacent to a highway from which coal merchants can collect a supply for subsequent delivery to their customers. At the extreme left of the map is Well Street. There is a coal stay (staithe) at the junction of Well Street and Hall Ings. This is evidently operated by J.J. & Co. who must be James Jarrett of Low Moor Iron Company. The ‘new road’, running diagonally across the centre of the map, later became known as Leeds Road. This dates the map to later than c.1825-30 during which years this new turnpike to Leeds was constructed by the Leeds & Halifax Turnpike Trust. Wakefield Road, Bridge Street, and Hall Ings are all in their present positions. Leeds Old Road is now Barkerend Road. As far as I can tell the numbered areas represent fields. Another staithe is present, which was also known as the Eastbrook coal staithe. Its designation clearly represents John Sturges (or Sturgess) & Co. of the Bowling Iron Works. There were two original partners of this name, father and son, but they were both probably dead by the time this map was created. The ‘new rail road’ drawn is in fact a mineral carrying tramway bringing coal in trucks to the Eastbrook staithe, by rope haulage, from the iron works. The trucks may have been returned filled with imported limestone, needed for iron smelting, which would have arrived at the nearby canal basin from the quarries at Skipton. The tramway was closed in 1846 and the area is marked as an ‘old staithe’ in the first OS map of the area.

How things have changed since the times of these maps. The dye works has gone, deep-mining of coal in the UK is finished, and UK iron and steel production hanging on by its fingertips.